Opinion | Hong Kong should no sooner erase its colonial past than Beijing should demolish the Forbidden City

- Hong Kong was ceded by the Qing Empire to the British Empire as a consequence of war, but then the Manchus came to power in China by force of arms. When regimes erase vestiges of vanquished foes, the sum of human knowledge is poorer for it

His achievement was, in a material sense, towering: both the university and the English-speaking world would probably have been different without him. That he was an enthusiastic colonialist and held views that some may consider repugnant is scarcely surprising.

The now unfashionable English novelist L.P. Hartley put it best when he wrote: “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.”

That is not facile moral relativism, but an acknowledgement that we, in contemplating the catalogue of history, are bound to the assumptions and prejudices of our own age, and perhaps cannot truly comprehend the conscience and motivations of those who came before us.

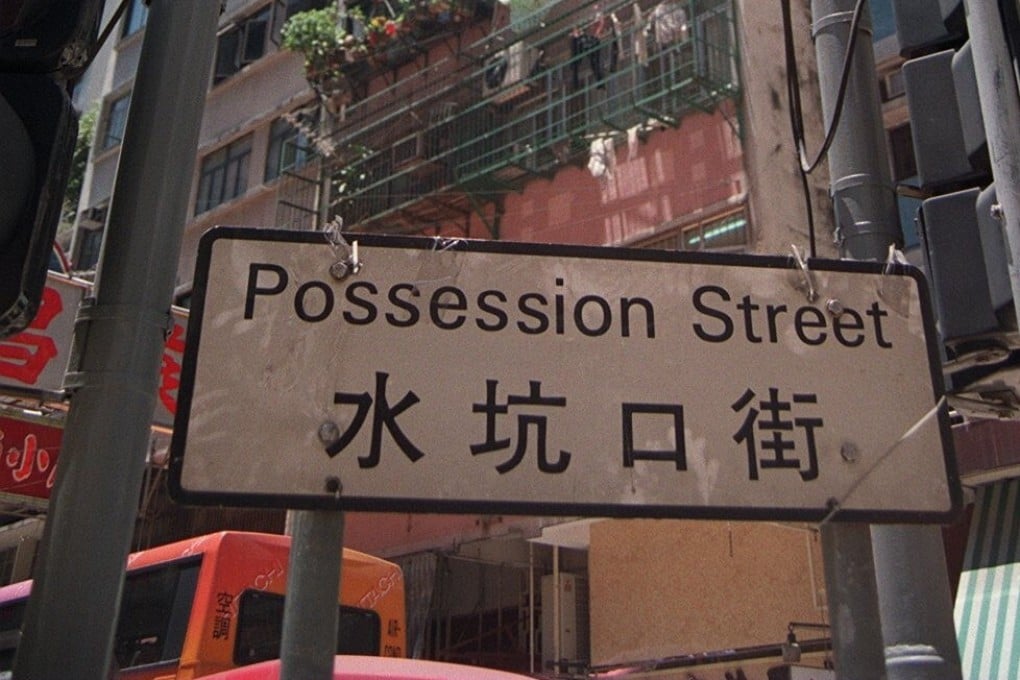

So we come to Hong Kong, where the past is in danger of becoming a battlefield for competing narratives that say more about present discontent than anything meaningful about our history.

03:06

Chinese emperor's ‘teapot’ found in clear-out of UK garage could sell for as much as US$636,000