Advertisement

Opinion | To lead, China must learn how to win friends and stop coming across as a bully

- As the Sweden example shows, Beijing’s way of dealing with criticism is eroding its soft power. China needs to avoid alienating others and learn how to influence people if it is to cement its place at the top

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

96

It is often said that Beijing political elites are encouraged to read the works of the great thinkers of the West. The theory is that reading Alexis de Tocqueville and Thucydides will allow an insight into the Western mind that will be useful in replicating the West’s global success.

One slightly less highbrow tome they might want to put on the reading list is Dale Carnegie’s 1936 classic How to Win Friends and Influence People. The original self-help book has some advice for countries wanting to win over the world, with tips that include “how to change people without giving offence”, “the only way to get the best of an argument is to avoid it”, and “make the other person happy about doing the thing you suggest”.

That might all be useful instruction for a country that is, rightly or wrongly, increasingly being seen as an international bully.

Advertisement

In many ways, China has had a good pandemic. It has shown that its system is robust enough to deal with the shock, and its economy is on track to be one of the few worldwide to end 2020 in the black.

It has been a different story for the country’s soft power, however. At the start of the Covid-19 emergency, Beijing made a concerted effort to sway global opinion with its “mask diplomacy”, dispatching planeloads of medical supplies and professionals to all corners of the Earth to show that it could be a responsible citizen – and leader – of the world.

04:45

China’s most-senior diplomats, Wang and Yang, conclude back-to-back visits to Europe

China’s most-senior diplomats, Wang and Yang, conclude back-to-back visits to Europe

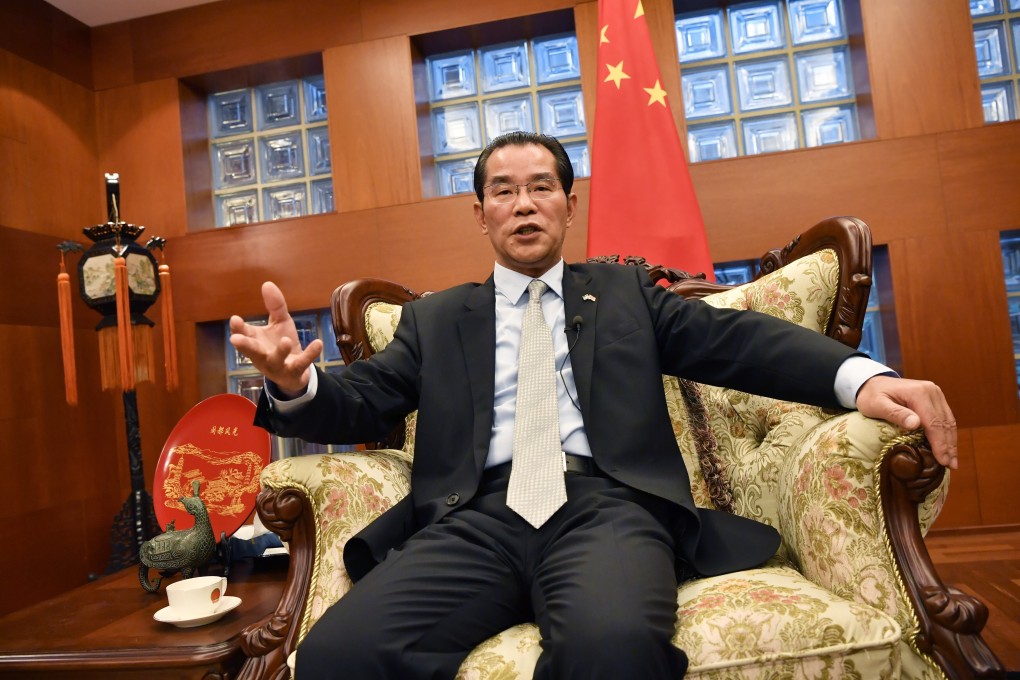

These efforts, though, have been undermined by some of the other headlines that China has generated this year, particularly in the West. “Wolf warrior diplomacy”, which sees Chinese diplomats get tough with foreign criticism of the country, might be popular at home. Abroad, however, it is alienating many countries that it wants to become close to.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x