Advertisement

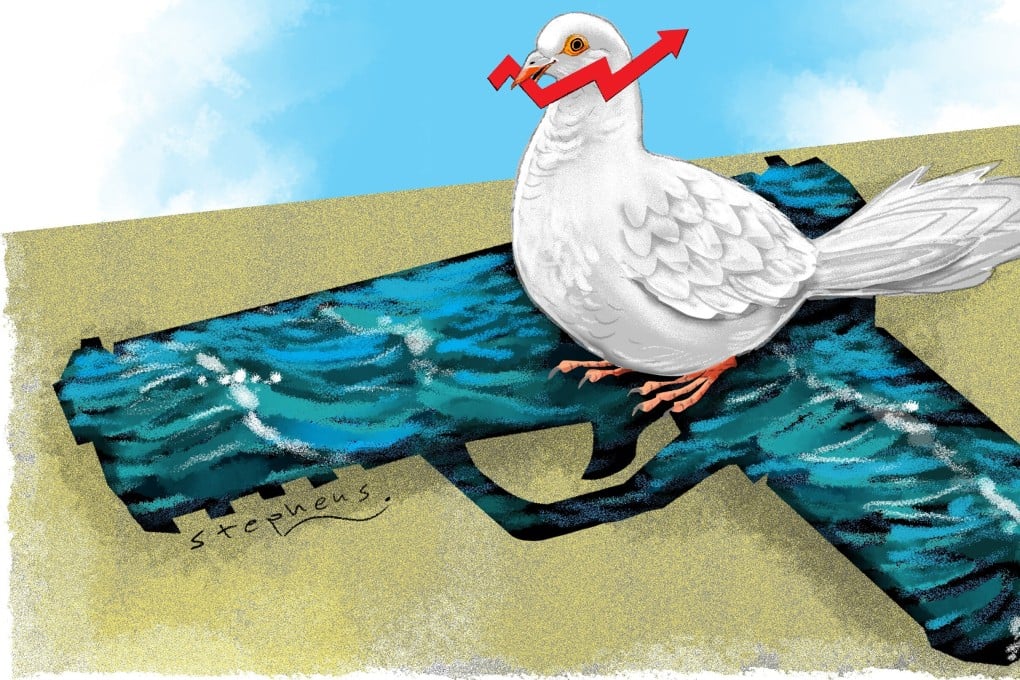

Opinion | South China Sea: how Asian nations can find peace and profit together

- Countries could agree to recognise current realities as de jure ownership in exchange for rescinding exclusive maritime rights

- A joint company could be set up to manage shared undertakings in the sea, with revenue to be distributed among all littoral states

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

13

Recent flare-ups from the Caucasus to the Himalayas are a reminder that “frozen conflicts” are never really so. They are always a trigger pull away from a sudden shift towards violence.

This is certainly true with the South China Sea, where there are many fingers on many triggers. China has reclaimed and militarised various rocks and reefs, Vietnam is now doing the same, the US Navy is conducting freedom of navigation operations while supporting the Philippines and Vietnamese navies to assert themselves, and Britain has deployed a carrier to the region.

As one of the world’s most strategic maritime trade corridors becomes more claustrophobic, it has also become more confused and dangerous.

Advertisement

Throughout Asian history, great civilisations have expanded and contracted across vast terrestrial and maritime spaces. In the past century, Japanese imperialism, decolonisation, Cold War proxy competition and China’s dramatic rise have left an indelible mark on East Asia’s patterns of interaction.

The confluence of these legacies forms the complex backdrop to disputes such as in the South China Sea, where pre-colonial coexistence has morphed into intricate military and legal manoeuvring to exclusively demarcate what, for most of history, has been shared.

03:23

The South China Sea dispute explained

The South China Sea dispute explained

I’m just old enough to remember the diplomatic spirit of the late 1990s and early 2000s that animated the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia, which both China and India joined in 2003. One of the tragedies of the South China Sea is how national rivalries have sublimated across generations. Optimism decays, suspicions are reinforced and the military-industrial complex prevails.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x