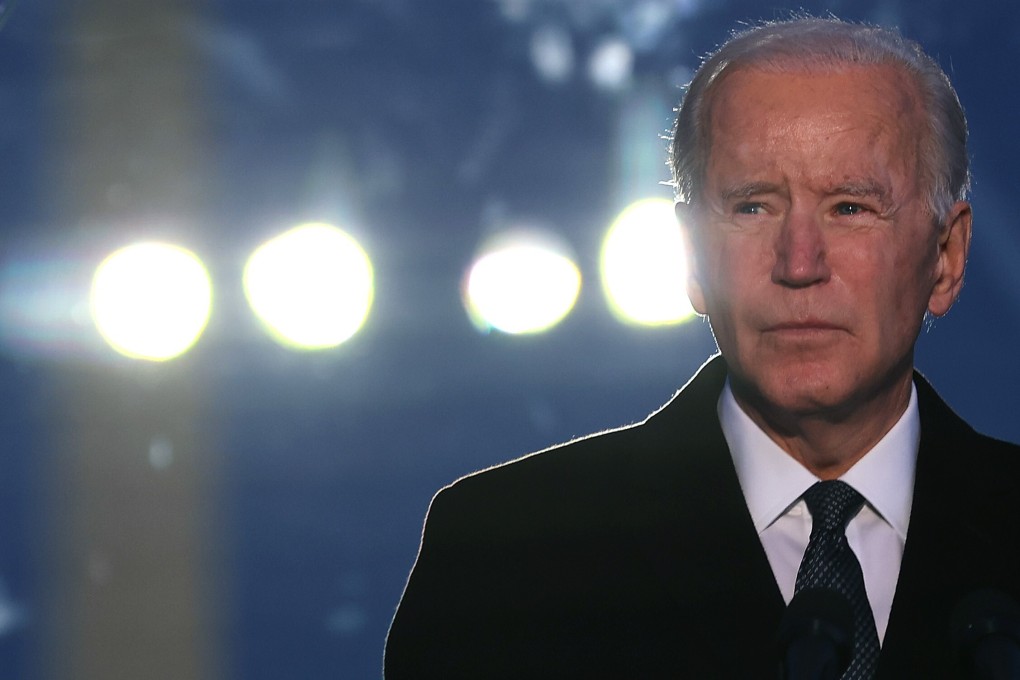

Opinion | Joe Biden’s dollar policy holds the key to a fairer global financial system

- How the US president steers the exorbitant privilege of the dollar is critical to the long-overdue reforms the global financial system needs to stop penalising the poor and emerging economies

Where is Wall Street going? Finance is supposed to serve the real economy (Main Street), but the US and global economies are in the midst of a pandemic and recession, while Wall Street profits are higher than ever.

Is this “socialism for the rich and capitalism for the rest”, as described by Morgan Stanley strategist Ruchir Sharma?

Since the 1970s, the rise of neoliberal free-market philosophy has boosted globalisation and trade liberalisation while pushing the deregulation of finance, labour, production and service markets. Globalisation has benefited many countries, but the benefits have been unevenly distributed.

04:58

Can globalisation survive coronavirus or will the pandemic kill it?

In the 1970s, American banks innovated into investment and private banking. Unfortunately, their excess lending led to the 1980s Latin American debt crisis. When competition arose from Japanese banks, American and European banks created the Basel Accord to ensure equal competition for all banks.