How China’s green finance slowdown threatens global climate ambitions

- Growth in China’s green financing, even for its much-touted green bonds, appears to be stalling, as environmental priorities take a back seat in a year when the economy has struggled to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic

According to the PBOC itself, the green proportion of bank loans, which makes up more than 80 per cent of green financing in China, has only grown from 8.8 per cent in 2013 to 10.8 per cent by 2020, only slightly faster than overall credit growth. Even as total bank credit continues to grow at above 10 per cent a year, the green proportion must increase simultaneously.

39:35

Sustainability: Green bonds to help drive China's push towards carbon neutrality

The expected launch of a massive national green fund has failed to materialise; the National Green Development Fund was launched last summer but has a meagre US$12.6 billion at disposal.

The emphasis on green finance as a tool towards meeting climate ambitions is a reasonable approach in an age where the economy is increasingly dependent on the financial system. China sees green finance as a critical tool for carrying out a green transition of its economy alongside, for example, reforming the electricity system, shifting subsidies from fossil fuels to renewable energy, and setting national and local green targets – similar to the path taken by the European Union.

But while targeted policies in China gave way to fast growth for the green finance industry a few years ago, we are no longer seeing the expected and needed on-the-ground impact of recent policy roll-outs.

A total of 17GW of new coal plants were approved in the first half of 2020, more than the two previous years combined, and around three-quarters of the global capacity installed in 2020. According to Global Energy Monitor, this takes China’s coal capacity under construction or development to a staggering 250GW, which is more than the US’ entire capacity.

The lack of green priorities in the Covid-19 recovery is evident in work done by Vivid Economics’ comparison of stimulus packages. While the EU allocated 37 per cent towards green purposes, China handed out more support to fossil fuels than to green transition projects, ending up with one of the least green stimulus packages globally. If climate issues trickle down to the bottom during turbulent times, China will not make steady climate progress in an uncertain world.

But green financing was already stagnating in 2018 and 2019, suggesting that Covid-19 is not the source of the slowdown. Rather, financial system regulators and financial institutions are waiting to see what effects the more ambitious climate goals set in the past few years will have.

01:24

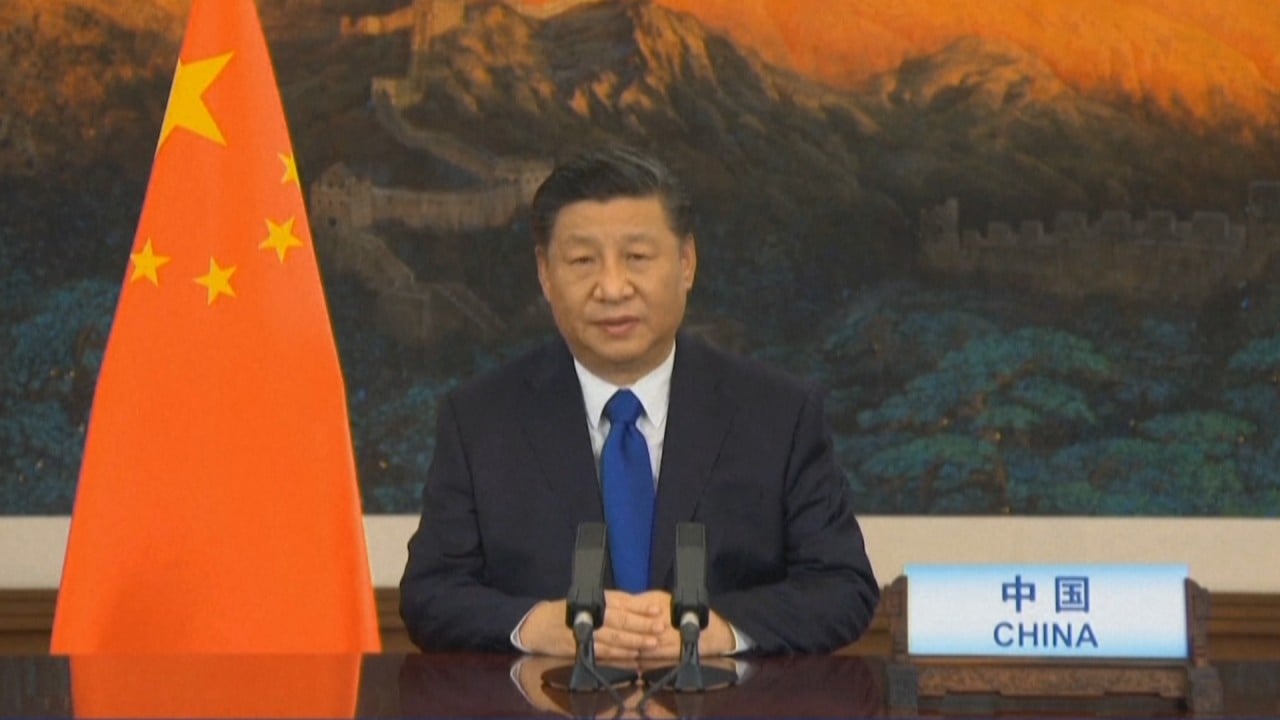

China to reduce carbon emissions by over 65 per cent, Xi Jinping says

Yet, all this is expected to be formalised in 2021 when the next five-year plan is launched in March. China is known to under-promise and overachieve on climate issues, so leaders may wish to achieve peak emissions much earlier than 2030.

As the most authoritative document on the Chinese economy, the five-year plan will have immediate effects on the market. This year will also see the next session of the UN climate negotiations in Glasgow, at which countries have to submit revised and improved climate plans.

While the 2060 target is a new addition certain to be included, the 2030 peak, first announced in 2015, is more likely to be pushed forward. Only once these two policies are in place will we know at what pace the green transition will take place, and consequently, how fast the financial system needs to be made greener.

Mathias Lund Larsen is senior research consultant at the International Institute of Green Finance at the Central University of Finance and Economics, Beijing