Art censorship: why the Hong Kong government has no business playing cultural gatekeeper

- Bureaucrats have a dismal track record when it comes to deciding what can be exhibited. Much better to leave it to the arts professionals

- If Hong Kong’s image as an open, tolerant and cosmopolitan city is damaged, the hard work put into building its art infrastructure will be wasted as well

Back then, artists who wanted to participate in the all-important yearly Paris exhibition had to submit their works to a government-sponsored panel for vetting. The panel favoured conservative, traditional paintings. But in 1863, Europe’s art scene was brimming with new ideas. The official panel didn’t get that – and rejected two-thirds of the works submitted.

The artists and their supporters rallied and created an alternative exhibition they called “Salon of the Refused”. The exhibit included paintings by Manet, Pissarro, Whistler – masterpieces that are the foundations of Impressionism, a movement that changed Western art forever. A stunning artistic success, the salon was also a hit: it drew a daily crowd of more than a thousand, who pushed to get in.

Here in Hong Kong, we are in the process of opening the West Kowloon Cultural District, a project that has been more than 20 years in the planning and which represents around HK$70 billion (US$9 billion) in investment. The M+ museum is slated to open this autumn, and the Palace Museum will follow in 2022.

The completion of the district couldn’t come at a better time. In the upcoming year, the global arts scene is set to revive after a difficult year of pandemic-related art fair cancellations and museum closures. Meanwhile, over the past decade, art has emerged as an important driver of Hong Kong’s economy.

The opening of the West Kowloon Cultural District should secure Hong Kong’s status as one of the world’s key art centres. The central government supports this; Beijing has designated Hong Kong as a hub for arts and cultural exchange between China and the rest of the world in the 14th five-year plan announced recently.

But if Hong Kong’s image as an open, tolerant and cosmopolitan city is damaged, the hard work we have put in to build its art infrastructure will be wasted as well. That’s why I’m surprised to hear calls for the Hong Kong government to take charge of supervising and even censoring the art shown in our museums and galleries.

Such a move would put us at risk of losing our global reputation – we would be imperilling an economic sector in which we have invested years of effort and billions of dollars.

Of course, I believe that any art exhibited in the city absolutely should not violate the laws of Hong Kong. But it’s important to make a distinction between what is illegal and what is only controversial. Remember that art often challenges our preconceived ideas. Indeed, that is the job of art in society.

So we need to be careful about slapping a label of “illegal” or calling for a ban on works of art merely because some members of the public personally don’t like them.

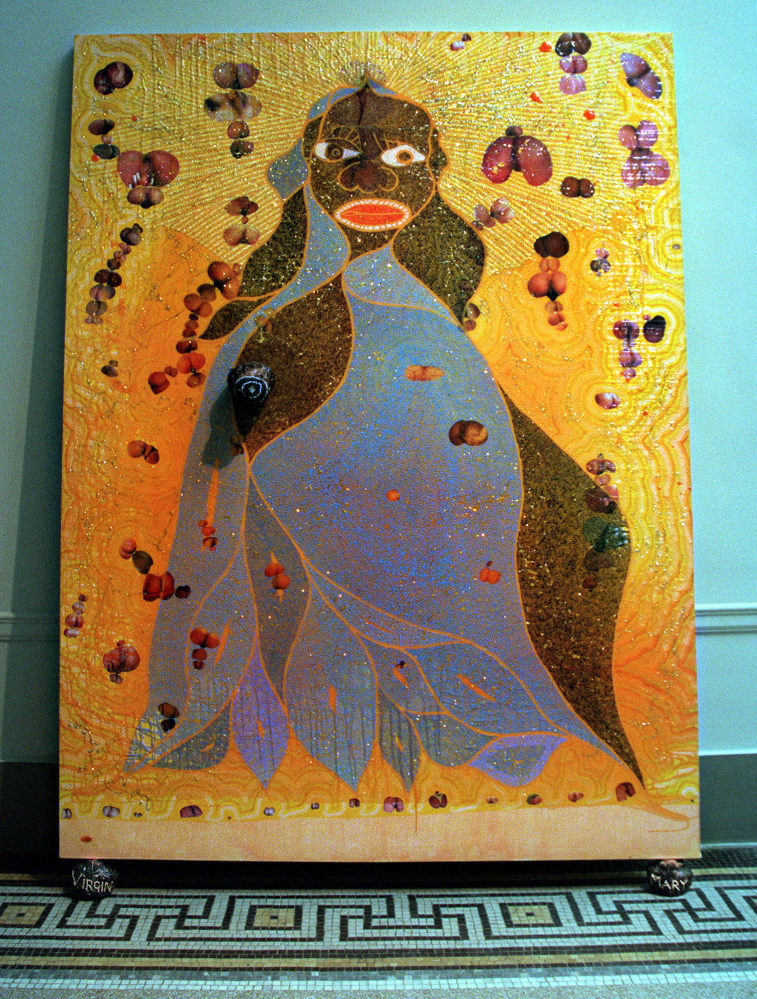

Such actions can end up making a city look very foolish. In 1999 in New York City, capital of the art world, then mayor Rudy Giuliani spent months trying to shut down an art exhibition that contained a work he found offensive – a painting by British artist Chris Ofili of the Virgin Mary decorated with dried elephant dung.

New Yorkers and art lovers worldwide rallied against the mayor’s clumsy attempt to interfere with the museum’s decision. Good sense prevailed, and the show went on.

In 2015, that Ofili work sold for £2.9 million. It now sits in New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Works by Impressionists sell for tens of millions of US dollars. Governments and bureaucrats have a dismal track record when it comes to cultural gatekeeping.

I think it’s a much better idea to entrust these decisions to professionals: curators and museum directors familiar with Hong Kong society. Curators and arts professionals bring invaluable knowledge of current global and local art trends to their decision-making.

They are in the best position to help us define and grow our arts scene as we open the West Kowloon Cultural District, and a promising new era of art in Hong Kong.

Bernard Chan is convenor of Hong Kong’s Executive Council