Hong Kong democracy: Beijing has dashed decades of hopes with radical reforms

- Democratic development in Hong Kong could have been China’s greatest achievement in the city. How would Hong Kong have evolved if Beijing had permitted universal suffrage for the chief executive election as early as 2007?

- The recent electoral reforms, which leave little, if any, room for the opposition, mean we will never know

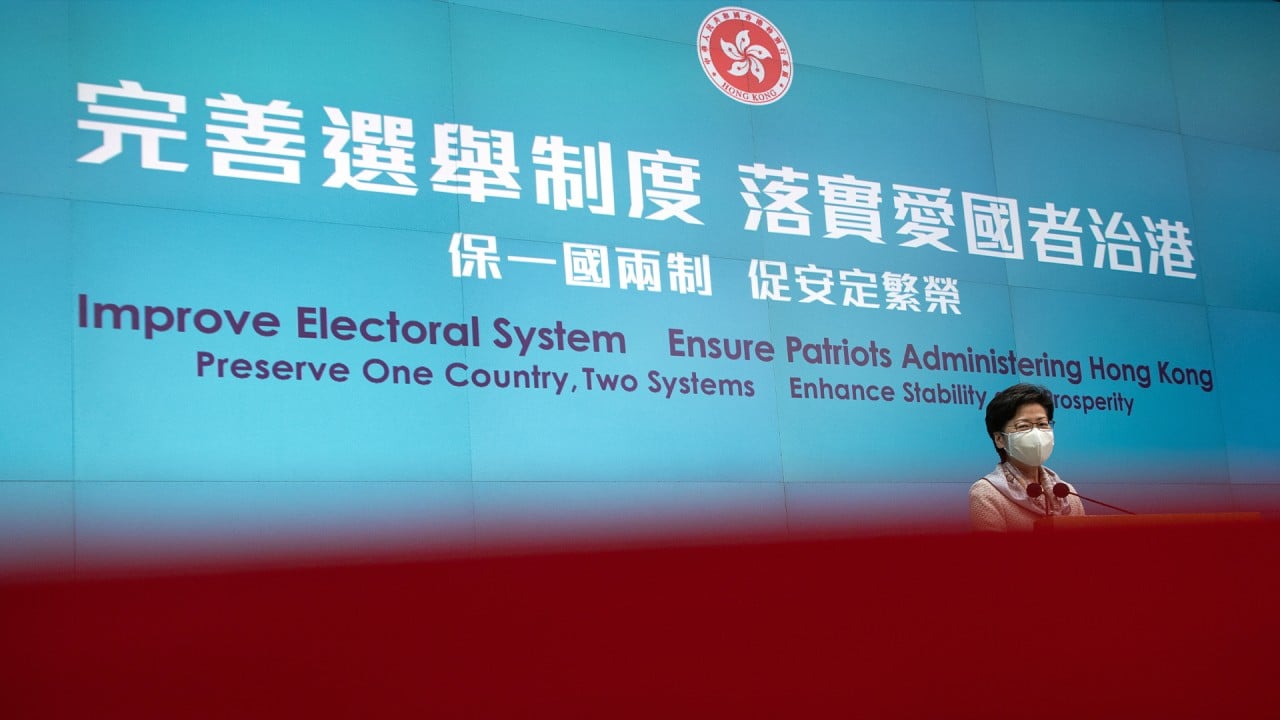

Full details of the reforms were not revealed until after they had been set in stone, with the National People’s Congress Standing Committee approving the relevant constitutional changes.

The new system goes even further than expected in creating barriers to entry for any democrat bold enough to stand for election. Nothing has been left to chance.

This is, tragically, the end of hopes dating back almost 40 years that Hong Kong could become a part of China where people can freely vote for candidates of their choosing and stand in elections for the chief executive and Legislative Council.

The changes appear to be designed to remove or restrict any part of the election system in which democrats – radical or moderate – have enjoyed a measure of success. Over the years, the opposition has increasingly made inroads into a system already designed to limit their influence.

The impact on the legislature, expanded to 90 seats, will be even greater. The opposition has long enjoyed success in the directly-elected constituencies. Those seats will now be cut back from 35 to 20, the smallest proportion since the first post-handover election in 1998. Ten constituencies will each elect two lawmakers. This, given the fairly equal political divide in Hong Kong, means the democrats are likely to win 10 of those seats at most.

As Beijing overhauls Hong Kong’s electoral system, is the city reaping what it sowed?

The biggest share of seats in Legco – 40 seats – will be chosen by the Election Committee. The remaining 30 will come from small functional constituencies which have also been revamped in a way that will make it harder for opposition candidates to win.

All election candidates will need at least two nominations from each sector of the Election Committee. This is an extremely high threshold. It is difficult to see even the most moderate democrats reaching it. Probably a token few will be allowed.

On top of all this, a new vetting committee, comprising senior government officials, will screen out candidates deemed not to be sufficiently “patriotic”. That committee will act on information provided by the national security police. And, in a surprise development, a state leader will act as a “chief convenor” to oversee elections. Precisely what this means is not yet clear.

The development of a democratic system in Hong Kong could have been China’s greatest achievement with regard to the city. Many will blame the democrats for rejecting a limited form of universal suffrage for the chief executive election offered in 2014 and embarking on a more radical course.

The city’s democratic dream might then have been realised. Perhaps it would have led to better governance, more inclusive policies, and the resolving of long-standing problems such as the wealth gap and the housing crisis. Maybe not. Now, we will never know.

Cliff Buddle is the Post’s editor of special projects