Why US and China’s push to set up rival power blocs are likely to fail

- China’s biggest ally Russia has concerns about Beijing’s influence in its backyard while US allies in the Asia-Pacific favour neutrality and maintaining Chinese ties

- Meanwhile, the middle powers from Japan and India to Australia and the EU have every incentive to prevent a ‘digital iron curtain’ and outright war

“Gradually, then suddenly,” said one of Ernest Hemingway’s characters when asked how one goes bankrupt. A similar dynamic has taken hold of the decades-old Sino-American detente, which transformed global politics for the past half-century but is now on the ropes.

Instead of converging on shared interests, the United States and China are rapidly nurturing rival power blocs, creating a perilous situation that eerily resembles the heyday of the Cold War.

Yet, amid a raging pandemic that is devastating the global economy and driving millions into extreme poverty, the last thing the world needs is a new cold war.

As veteran US diplomat Henry Kissinger notes, the US recognised China’s immense potential as a partner in a stable and prosperous international order.

Thus, over the next half-century, both Republican and Democratic administrations carefully nurtured deeper economic engagement with the Asian powerhouse and avoided direct confrontation.

As president Bill Clinton put it, integrating China into the world economy is “in our larger national interest”, since it “represents the most significant opportunity that we have had to create positive change in China”.

It was precisely within this context of unprecedented economic interdependence, the so-called Chimerica era, that major cracks within bilateral relations began to appear.

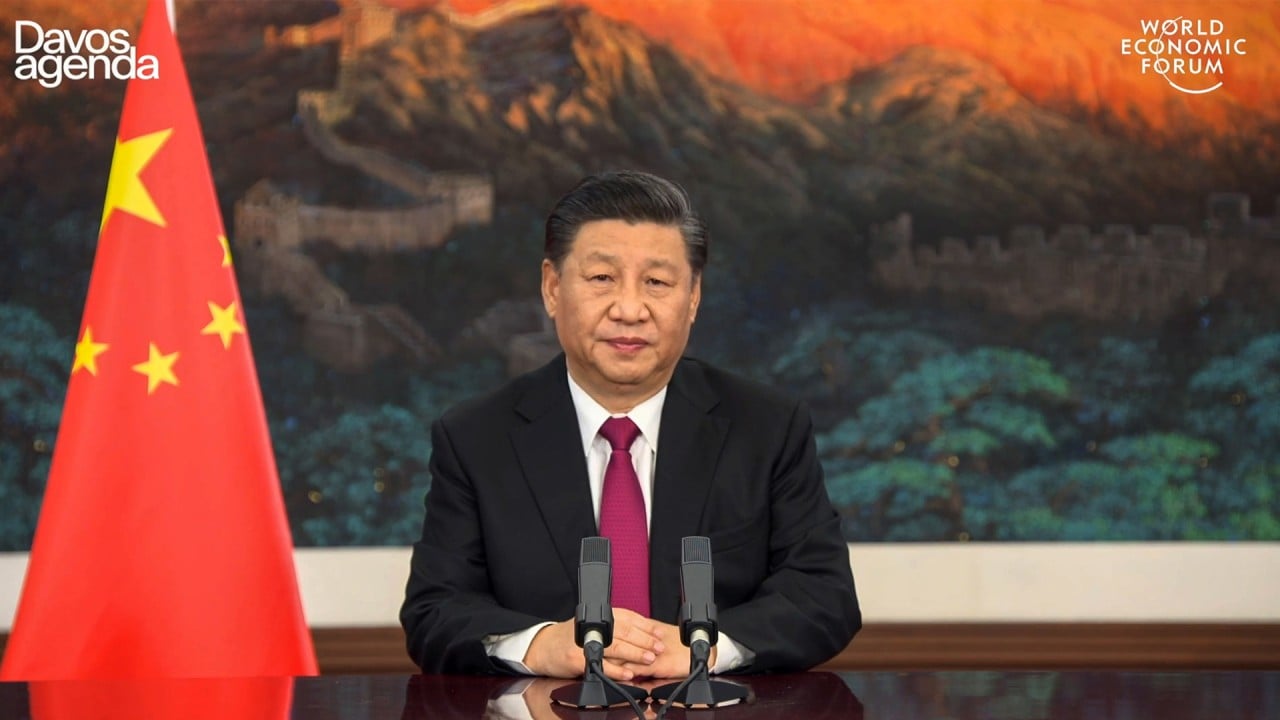

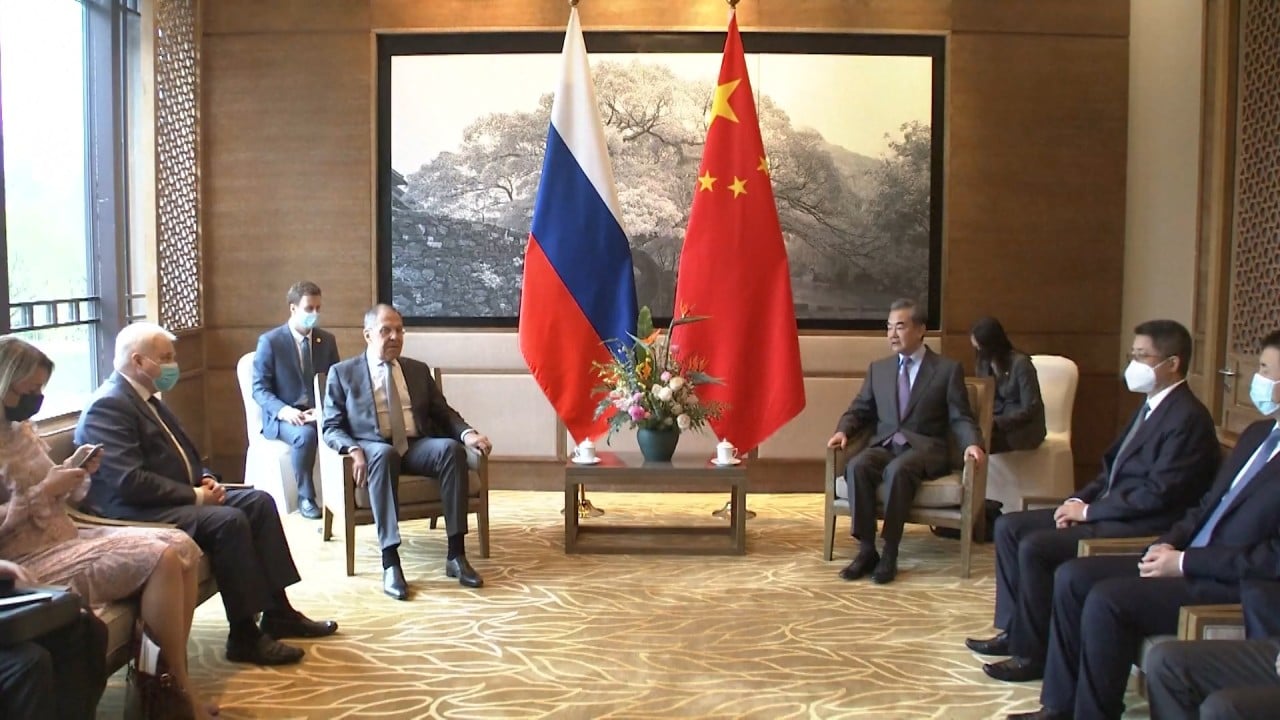

Tellingly, right after their much-anticipated meeting, both Chinese and American veteran diplomats proceeded to build rival alliances.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi embarked on a diplomacy tour that included a high-profile meeting with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and visits to key West Asian powers, including Turkey and Saudi Arabia, which have been at loggerheads with Washington over strategic and human rights issues.

For the first time in recent memory, almost all major powers across the Eurasian land mass, from China to Russia and Turkey, are confronting robust Western sanctions, underscoring the vast potential for a Beijing-led counter-alliance against Washington.

There are, however, three factors that could prevent an inexorable march towards a new cold war in Asia. To begin with, in key regions such as Southeast Asia, there is zero appetite to choose one superpower over the other.

Traumatised by Cold War conflict, even US treaty allies such as the Philippines and Thailand prefer to maintain stable and fruitful ties with China.

Southeast Asia cannot afford another neocolonial great power rivalry

The same can be said about the bulk of Asian and Eastern European nations, many of which have strong military ties with Washington but are also increasingly dependent on Chinese economic largesse, especially with a pandemic recession brewing.

Meanwhile, there is no indication that either Turkey or Saudi Arabia are in a position to ditch Washington, their predominant source of military technology and training, in favour of Beijing, which is yet to become a decisive power in the deeply unstable Middle East.

How China’s Middle East charm offensive succeeded despite affecting little change

Finally, all the major “middle powers”, from Japan and India to Australia and the European Union, recognise that a zero-sum superpower rivalry is not in their interest.

Notwithstanding shared concerns over Beijing’s rising assertiveness, they have as much incentive to prevent an unrestrained Sino-American military escalation as to stop the emergence of a “digital iron curtain” that would undercut fragile global economic recovery and threaten decades of globalisation.

The good old days of Sino-American detente may be over, first gradually then suddenly, but there is still a chance to prevent another cold war.

Richard Heydarian is a Manila-based academic and author of “Asia’s New Battlefield: US, China and the Struggle for Western Pacific” and the forthcoming “Duterte’s Rise”