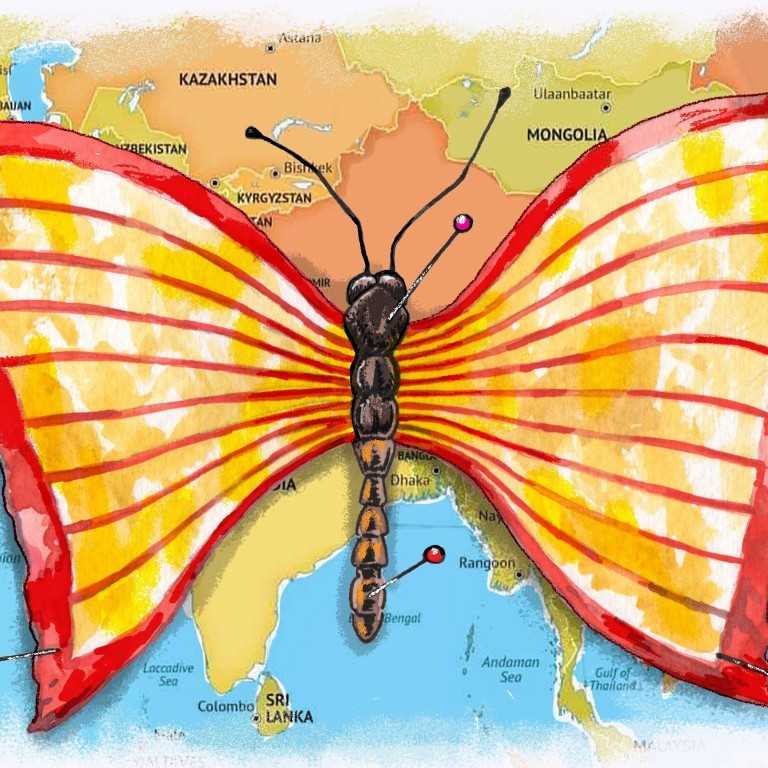

How the Myanmar coup and South China Sea disputes are deepening Asean’s irrelevance

- With Myanmar heading into a full-blown civil war and the South China Sea a powder keg of disputes, Asean’s ineffectual leadership has never been more obvious

- Asean’s insistence on consensus sounds good on paper, but in practice it is a recipe for institutional dysfunction

“An era can be said to end when its basic illusions are exhausted,” Arthur Miller once observed. In the same vein, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), a once promising regional organisation, is confronting its own moment of truth.

The raging civil war in Myanmar, and the festering disputes in the South China Sea, are cruelly exhausting the basic illusions of supposed Asean “centrality” in shaping the post-Cold-War order in Asia. Unless Asean rethinks its woefully dysfunctional decision-making structures, and develops decisive leaders in its ranks, the regional organisation will fade into irrelevance.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. Without a robust and coherent Asean, the whole Indo-Pacific region could sleepwalk towards a new cold war, with dire consequences for Southeast Asian nations.

Time and again, the regional organisation has unwittingly served as a legitimisation platform for Myanmar’s brutal generals. In the late 2000s, Asean enthusiastically endorsed cosmetic political reforms by the junta, which temporarily empowered a more reform-minded civilian leadership without stripping away the prerogatives of the military.

05:18

SCMP Explains: How did Myanmar’s military become so powerful?

Yet again, Asean demurred from a decisive response, including the threat of temporarily suspending Myanmar’s membership without an immediate restoration of the democratically elected civilian government.

Myanmar crisis requires Beijing to lead – and work with Washington

Instead, only a handful of Asean members issued categorical condemnation of the junta’s brazen overthrow of a democratically elected government, while both Cambodia and Thailand argued that the coup is purely an internal affair.

The tepid and vaguely-worded “consensus”, which generically calls for an end to ongoing violence and restoration of normal politics, lacks a clear timeline and enforcement mechanism. Pro-democracy forces have lambasted Asean for legitimising the junta.

Why is Germany sending a frigate through the South China Sea?

Moreover, China-friendly Southeast Asian leaders have either (as in Cambodia’s Hun Sen) called for omitting the disputes from regional discussions all together, or (as in Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines) instead chosen to blame outside powers such as the US for escalating tensions in the region.

With Asean pushed to the sidelines, it’s the US and China that are instead shaping the trajectory of the South China Sea disputes, with the Japanese, Indians, Australians and even Europeans now chipping in. The upshot is a dangerous and unfettered escalation in naval showdowns in Asia’s high seas.

02:37

Philippines sounds alarm over 200 Chinese ships in the South China Sea

At the heart of Asean’s growing irrelevance is its self-defeating insistence on consensus (muafakat), which sounds good on paper, but, in practice, is a recipe for institutional dysfunction. This is because Asean’s version of consensus is more like unanimity, which is close to impossible to achieve when urgent and high-stakes geopolitical issues emerge.

Moreover, the regional body also lacks the kind of visionary leaders such as Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew, Indonesia’s Suharto, and Malaysia’s Mahathir Mohamad, who collectively played a critical role in the growth and maturation of Asean under the impossible conditions of the Cold War.

Not all is lost, however. For instance, Asean can more regularly employ its majority-based and tried-and-tested “Asean Minus X” formula, which facilitated the quick and successful negotiation of, inter alia, regional trade agreements.

The regional body should also welcome more “mini-lateral” cooperation among its key members, whereby like-minded Southeast Asian states jointly coordinate their response to a specific crisis without hopelessly requiring the consent of regional naysayers.

After all, mini-lateral cooperation worked wonders in terms of joint patrols and counterterrorism operations, from the Strait of Malacca to the Sulu-Sulawesi seas, among key Asean members. Thus, the Southeast Asian claimant states of Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines should explore their own version of a code of conduct in the South China Sea in accordance with international law.

Ultimately, Asean needs decisive core leadership and an empowered bureaucracy to effectively shape its own neighbourhood and the broader Indo-Pacific. Otherwise, it will end up as an exhausted illusion, rather than the driver of regional integration.

Richard Heydarian is a Manila-based academic and author of “Asia’s New Battlefield: US, China and the Struggle for the Western Pacific” and the forthcoming “Duterte’s Rise”