Advertisement

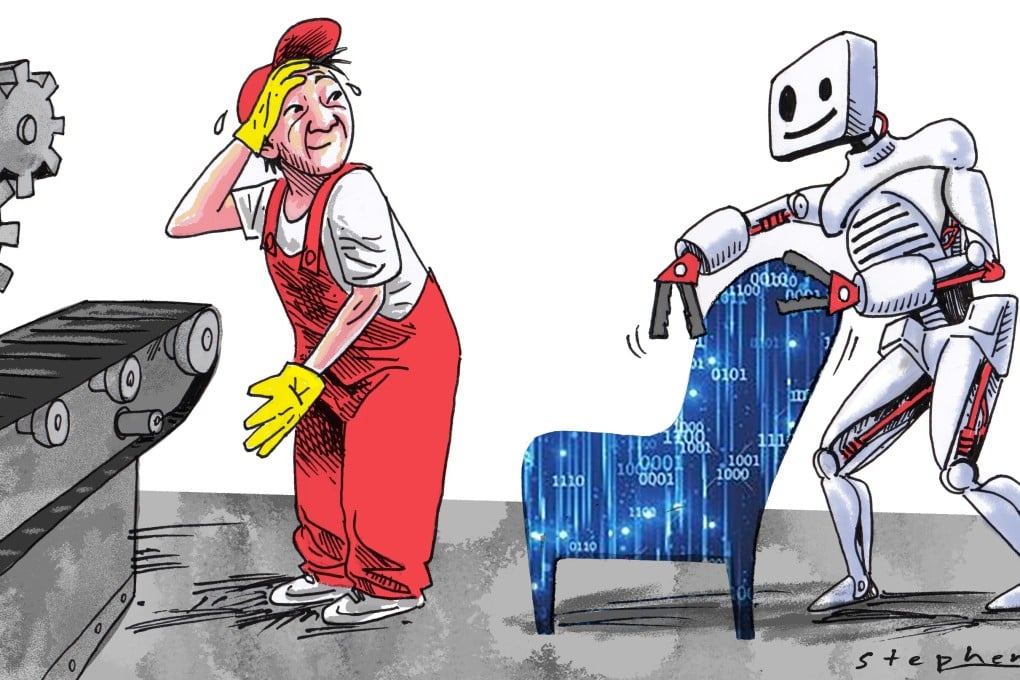

Opinion | Why China’s dire demographic news signals need to adapt, focus on productivity

- Ultimately, what really matters for dealing with an ageing society and a shrinking workforce is to make economic activities more robust

- China should also work to build up an attractive living environment to improve people’s quality of life, rather than focusing on quantity

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

2

The latest census on China’s population has confirmed the much-anticipated concern about ageing and low fertility. In 2020, China had a population of 1.41 billion people, an increase of about 72 million from 1.34 billion in 2019. This represents a smaller annual percentage rise of 0.53 per cent compared to 0.57 per cent from 2000 to 2010.

The proportion of the population aged 60 years or above and 65 and over increased to 18.7 per cent and 13.5 per cent, respectively. Based on United Nations definitions, China is an ageing society. The number of births was 12 million, down from 14.65 million in 2019, despite the relaxation of the one-child policy. The total fertility rate is 1.3 births per woman, well below the replacement level of 2.1.

The two major concerns, ageing and low fertility, are not uncommon and happen to other countries as well. What makes it particularly challenging is the speed and scale of the problem as China is the most populous country in the world, and it could have a spillover effect at the global level.

Advertisement

The impact of ageing on GDP has not been fully appreciated and understood. Based on our calculations, if there is no significant change in the fertility rate, the proportion of China’s working-age population will decline from 70 per cent at present to 60 per cent in 2050.

If the Chinese government aims to maintain an annual GDP growth rate of 7 per cent up to 2045, the output per worker needs to reach nine times the 2015 level, which would be extremely difficult. For a more realistic 3 per cent growth, labour productivity still needs to roughly triple by 2045.

10:42

China 2020 census records slowest population growth in decades

China 2020 census records slowest population growth in decades

It has yet to be determined whether China is prepared for the impact of a reduced workforce on GDP growth, the increase in older adults on the affordability of the country’s pension scheme and the sustainability of unbalanced urban and rural development.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x