Teaching tutoring centres a lesson won’t get to the root of Chinese students’ stress

- While President Xi Jinping is right to focus on the problems in the education sector, cram schools are only the tip of the iceberg

- Reform of the gaokao system is key to ending the unhealthy over-reliance on after-school tutoring

It’s not news that the education sector – especially off-campus education that starts from kindergarten and runs all the way up to grade 12 – is ridiculously lucrative.

It isn’t the only one to have collapsed overnight, and this isn’t the first time the central government has tried to rein in the industry. Reform has been discussed for decades; the last time the after-school education sector faced the wrath of the government was in 2018.

This time, the clampdown will reportedly focus on business qualifications of after-school tutors, false advertising and overcharging, as well as certain subjects and where and when classes can be held.

Turning education from an honourable profession into a business focused on profit with little regard for students’ real needs deserves public scorn and government intervention. The question is, what intervention is needed to address the problem?

01:34

Father trains dog to supervise his daughter as she does homework

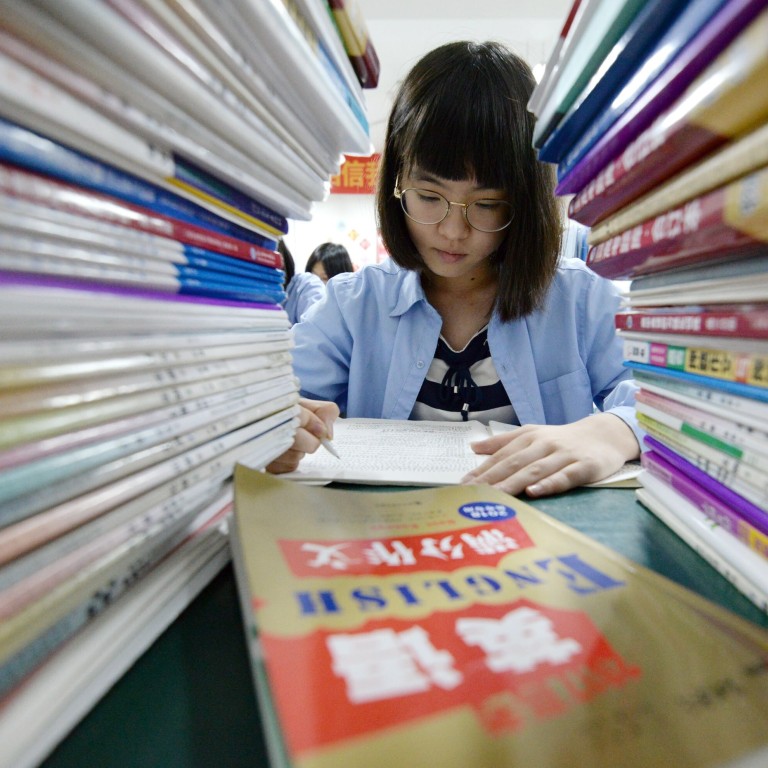

The after-school industry capitalises on parents’ blind faith that academic success will provide their children with greater opportunities and a better life. It feeds on the fear of missing out and of falling behind, simply because children did not excel in test taking, driving parents to give up their careers or channel all their money into cram schools and to make their children spend every waking moment studying.

For example, there have media reports about the “Haidian Huangzhuang moms” from the affluent Beijing district, home to renowned schools and universities – and cram schools. One of them told a newspaper: “Haidian moms don’t compare luxury bags or material things like where you live. The only thing anyone cares about is the child’s grades.”

But is banning after-school classes at weekends or outlawing advertisements enough to solve this social problem?

No amount of cracking down on tutoring centres can undo the belief that hard work and putting in the hours pay off. That’s why students are pressured into studying around the clock.

And so it is not the overhauling of cram schools but the reform of the gaokao system that is key to ending the unhealthy over-reliance on after-school tutoring. End the emphasis on exam scores, and the demand for cram schools will dissipate.

In fact, a happy side effect will be that teachers in regular schools will start to teach, and not just drill students for exams, as they do currently because of pressure to ensure university acceptance rates remain high.

Reading about “Haidian moms” should make us pause, not to judge, but to consider how alike we are. If there is one thing Hongkongers share most with our mainland brethren, it is this.

It is an attitude common to most Asian countries – we go over the top when it comes to trying to ensure that our children win at the starting line, or obliterate the competition along the way.

We may have the best intentions for our kids, but what about their well-being?

Alice Wu is a political consultant and a former associate director of the Asia Pacific Media Network at UCLA