Advertisement

Opinion | Why Asean-China relations will remain cordial, but not close

- As the global geopolitical focus shifts to Asia, Asean takes on greater salience for the major powers, particularly China

- While China and Asean have pledged in their recent meeting to take their partnership to ‘new heights’, given China’s actions in the region, Asean’s wariness is understandable

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

12

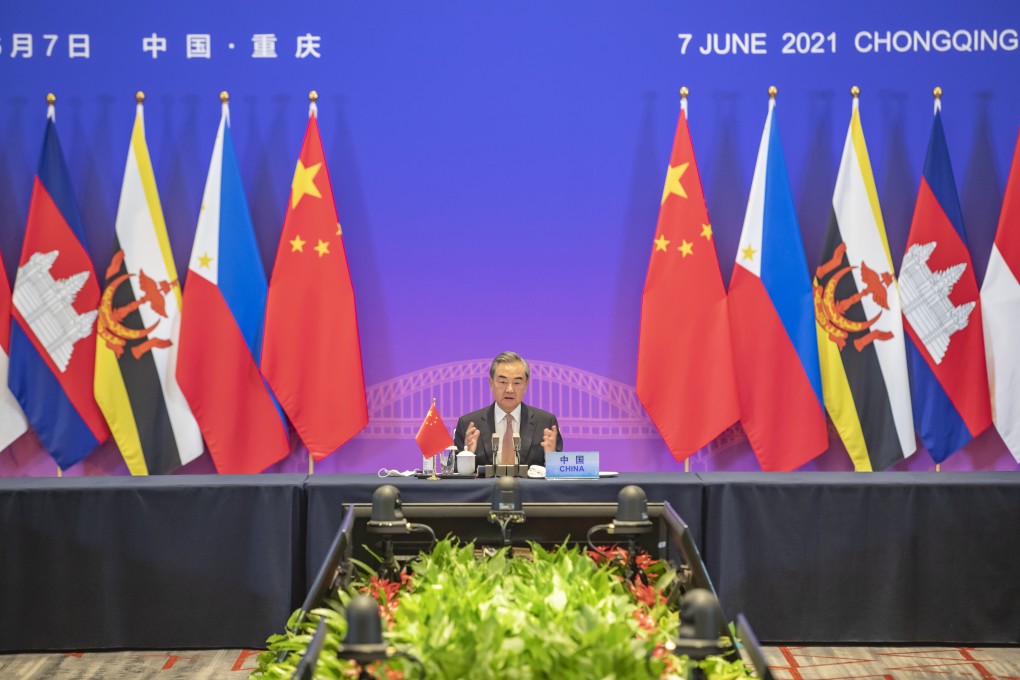

China hosted the foreign ministers of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations at a meeting in Chongqing on June 7-8 to mark the 30th anniversary of dialogue relations between the two sides. Given the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the region, China offered Asean its support by way of the supply and joint production of vaccines.

Further, the joint statement issued said both parties would “advance Asean-China Strategic Partnership to new heights by forging closer cooperation”. The subtext of this document and its larger geopolitical context merit scrutiny.

Bilateral interaction between Asean and China began in July 1991 when China was invited to the 24th Asean ministerial meeting in Malaysia. At the time, Asean comprised six nations.

Advertisement

Since its inception in August 1967, Asean has had a special relevance for the major powers. During the Cold War decades, the United States and the former Soviet Union had their own strategic objectives in relation to Southeast Asia and the nascent five-member Asean was nurtured by the US-led West as part of a containment strategy.

However, the end of the Cold War led to a radical rearrangement of regional geopolitics and, from 1991 onwards, China has emerged as an important interlocutor for Asean. Asean now has 10 members and has sought to maintain a delicate political and diplomatic balance when faced with major power rivalries.

In the last decade, the global geopolitical focus has shifted to Asia, and the Indo-Pacific has acquired a strategic contour. This has further accentuated the salience of Asean for the major powers and China in particular.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x