Advertisement

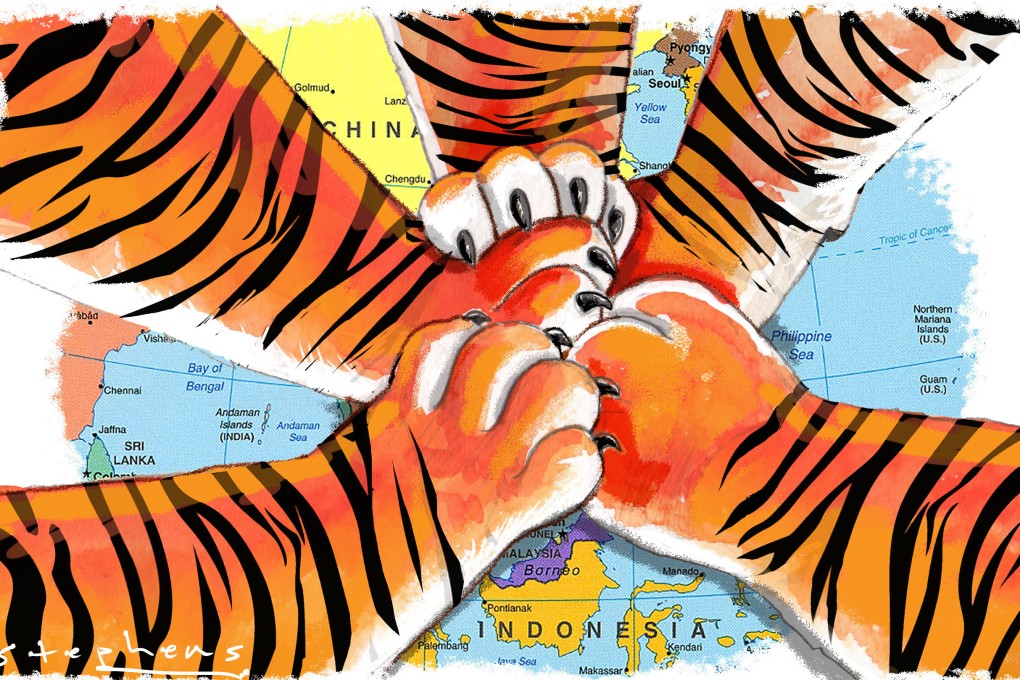

Opinion | How Asian societies’ premodern traits explain region’s success stories

- Asian societies differ from the West in their commitment to academic excellence and social solidarity as well as synergy between state and society

- A meritocratic system informed by Confucianism and Legalism is highly effective at regulating political order, socioeconomic affairs and interstate relations

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

5

Interest in the re-emergence of Asia has grown strong of late. It is important to remember that many elements that are seen as strengths of Asian governments and Asian society have historical origins.

The economic success stories of Japan and the East Asian tigers led scholars to point to the special roles the state played in Asian societies. The purposes and visions of these states appeared to be different from those that are familiar in the West.

Furthermore, Asian states’ competence in promoting economic development and improving people’s living standards in areas such as public health, among others, turned out to be significant. Asian society also appears to be different from Western societies in important ways. The high commitment to academic excellence and social solidarity quickly come to mind.

Advertisement

A strong synergy exists between the state and society, too. The willingness for members of society to work with government in implementing epidemic-fighting measures – such as social distancing and wearing masks, for example – was crucial in several Asian societies’ effective response to the Covid-19 outbreak.

Some of these strengths of the Asian state and society have historical origins. The Zhou dynasty was one defining period in Asian history. According to a recent study by sociologist Zhao Dingxin of the University of Chicago and Zhejiang University, some of the most essential characteristics of the Asian state and society were formed during this period.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x