Advertisement

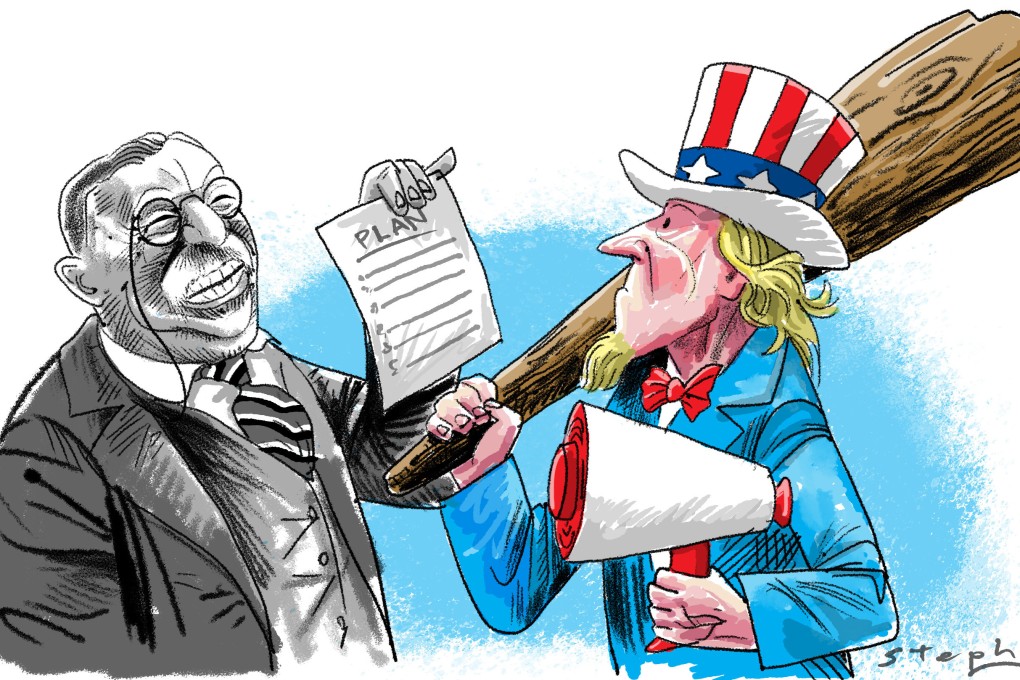

Opinion | In US-China tussle over Southeast Asia, America must do more than speak softly and carry a big stick

- Recent US diplomatic successes in re-engaging the region notwithstanding, the US needs a comprehensive strategy to compete with China

- The Biden administration will have to double down not only on its trade and military footprint, but also on its vaccine diplomacy

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

7

“Speak softly, and carry a big stick – you will go far,” said US president Teddy Roosevelt, who oversaw America’s transformation into what some see as a global empire a century ago. US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin, who oversees the world’s mightiest military, did exactly the same on his maiden visit to Southeast Asia.

As the first African-American Pentagon chief, he charmed his guests with a refreshing display of humility, openly acknowledging democratic challenges at home, especially the recent uptick in anti-Asian racism. In a major departure from Trump-era unilateralism, Austin also emphasised the importance of “integrated deterrence”, namely, US reliance on a network of allies and partners to combat shared threats.

And in a major diplomatic victory, his visit to the Philippines culminated in the restoration of the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA), which allows a large American military presence in the Philippines.

Seen as broadly successful by regional observers, Austin’s visit has also raised expectations of more concrete initiatives by Washington soon. To remain competitive against a resurgent China, the Biden administration will have to double down not only on its trade and military footprint, but also on its vaccine diplomacy amid a raging pandemic.

Advertisement

Austin’s Southeast Asian tour, which took him to Singapore and the capitals of Vietnam and the Philippines, couldn’t have come at a more critical juncture. Throughout the year, Southeast Asian policymakers and pundits had fretted about a lack of meaningful engagement by the Biden administration.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, who visited major European and Asian capitals in his first months in office, did not manage a summit with Asean until last month.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x