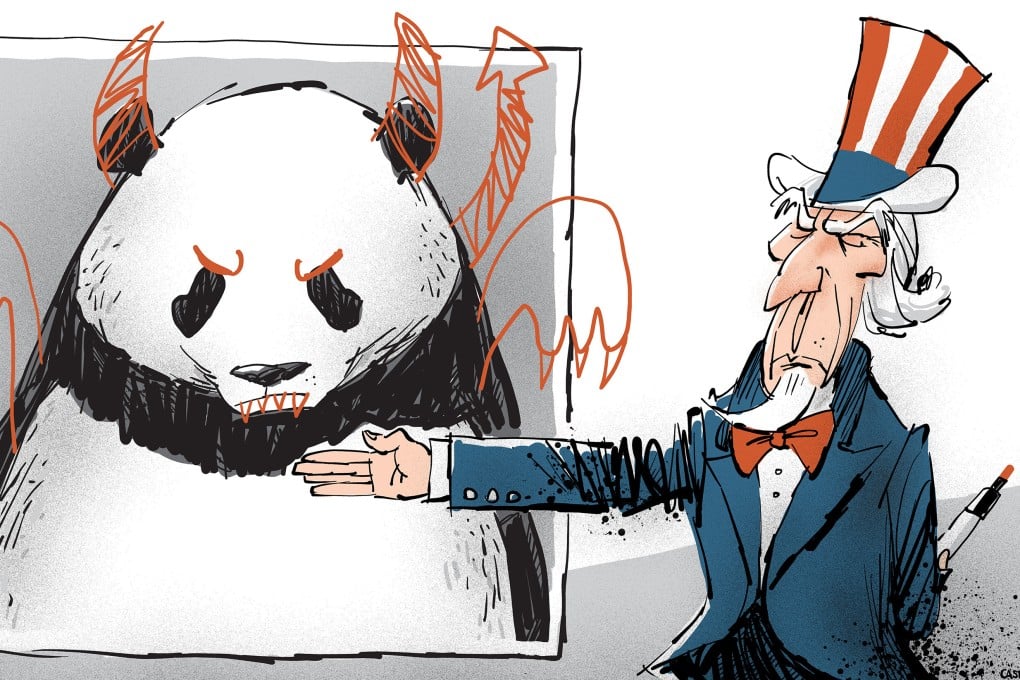

Opinion | ‘China threat’: why the US needs to rethink its dangerous obsession

- Casting China as a danger to national security needlessly raises tensions, hampers diplomacy and dehumanises Asians in America

- Reframing the narrative would allow Americans to better judge the challenges – and opportunities – presented by China’s rise

China “poses the greatest national security threat to the United States”, according to a joint statement from Republican Senator Marco Rubio and Democratic Senator Mark Warner. They assert that “our democratic values are threatened by China’s attempts to supplant American leadership and remake the international community in their image”.

It’s not the first time Washington has levelled this kind of accusation. Early in the Cold War, even though the Soviet Union had honoured most of its agreements with the US, the notion of the “Soviet threat” prevailed.

Hawks within the Truman administration – including a faction known as the Wise Men – alleged with little evidence that Stalin was bent on global hegemony through military means and that Soviet expansionism could only be contained by force.

The proposed solution, naturally, was for America to pursue what it was accusing the Soviet Union of plotting: militarisation and global hegemony.

And so it did. In his book The American Century and Beyond: US Foreign Relations, 1893-2014, American historian George Herring writes that the Wise Men “were generally pragmatic and realistic rather than ideological in resisting the Soviet Union. But they frequently exaggerated the Soviet threat to sell their programmes. Sometimes, they were persuaded by their own rhetoric or became its political captives.”