Shades Off | Patriotism should not lead to a single, Beijing-approved view of Hong Kong history

- In our attempt to bring Hong Kong’s account of its own history in line with the mainland Chinese version, there needs to be room to accommodate different points of view

History is fluid, being shaped over time by research and interpretation. A saying that it is “written by the victors” is also partly true.

Knowing that should have prepared me for a visit to the Hong Kong Museum of History. Still, I was surprised to read in the section on British colonial rule that “through three unequal treaties, Britain succeeded in illegally occupying the entire area of Hong Kong”.

A third pact in 1898 gave it control of the New Territories. Negotiating from a weak position can be interpreted as “uneven”, but is an agreement that leads to the handing over of territory “illegal occupation”?

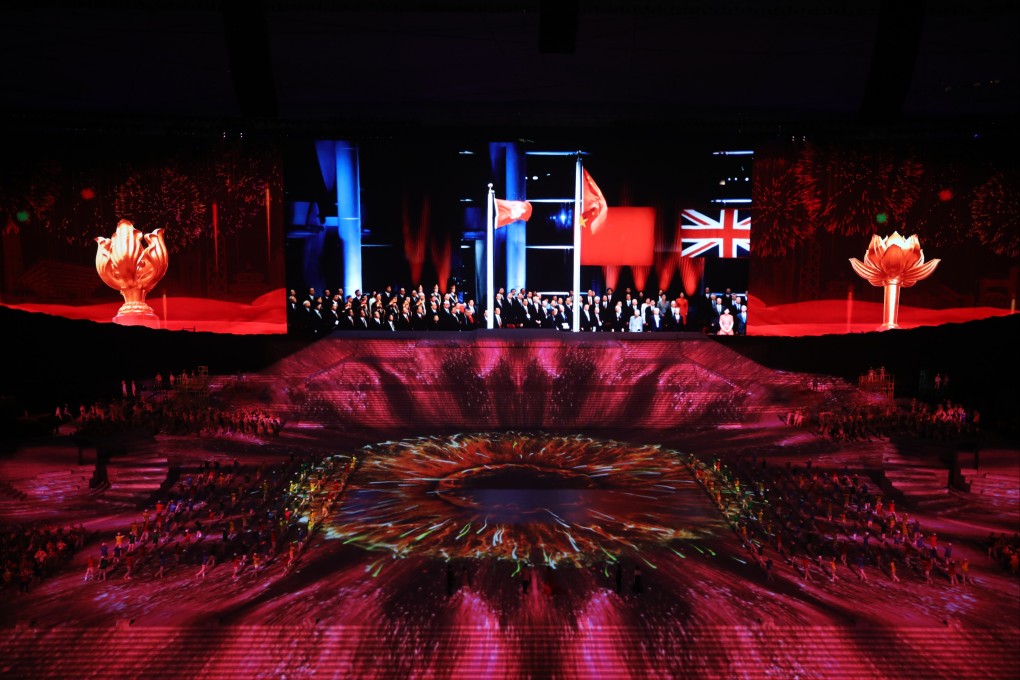

That is in keeping with the Chinese Communist Party’s narrative that, despite the treaties, China never gave up sovereignty of Hong Kong because the pacts were illegal and violated international conventions.