Opinion | Why Hong Kong children need to return to normal school days

- The EDB’s 70 per cent vaccination rule for school reopening seems neither scientific nor is it being applied equally

- Most students have not had a full day of school since 2020, but private schools can fully reopen as their facilities are deemed suitable for social distancing

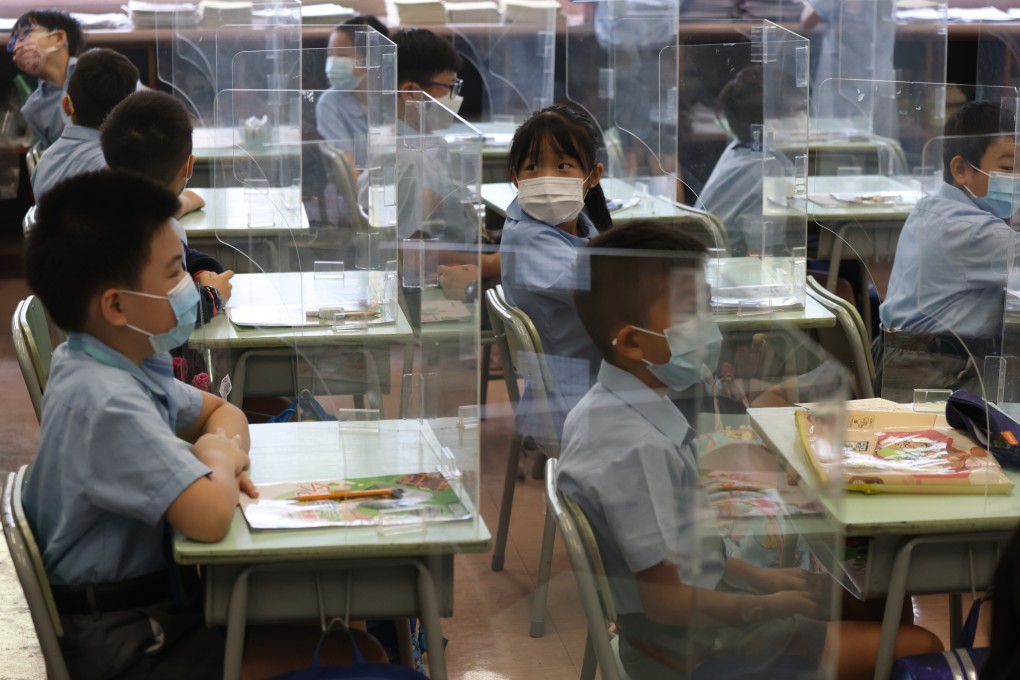

But there’s one area that’s conspicuously – and bafflingly – not normal. Schools. Most Hong Kong students have not had a full day of school since early 2020.

And, since under-12s aren’t eligible for vaccination yet, full-day sessions for kindergarten and primary school pupils “remain off the table for now, with no indication of when they might resume”, the Post reported.

The reasoning behind these rules is frustratingly opaque. The dangers of Covid-19 exposure during lunch are often mentioned as a reason for dismissing students at midday.

Yet, some are still allowed to eat at school, as long as their food is designated a “snack” rather than “lunch”. At many schools, including my children’s, this rule is interpreted to mean children can eat finger food, but are not allowed to use utensils. This hardly seems rational or scientific.