Advertisement

Opinion | How the Aukus security alliance raises awkward questions for China, and some US allies

- By focusing on the US, UK and Australia, the grouping leaves out key allies and partners, including France, Canada and New Zealand

- For Beijing, the partnership shows how its policies on Indo-Pacific countries, such as sanctioning Australian exports, can backfire

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

32

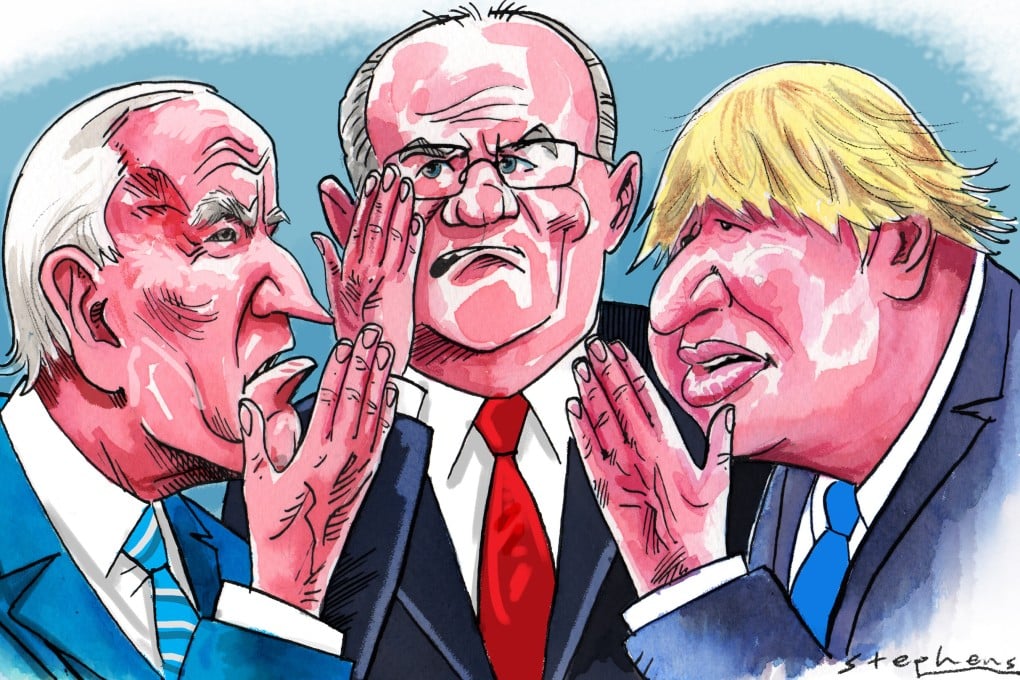

On September 15, something both significant and unsurprising happened. The United States, United Kingdom and Australia announced a new trilateral security partnership, known as “Aukus”, designed to share defence industrial information and collaborate militarily.

The agreement is significant because it adds a new element to the US-based Indo-Pacific alliance system. It also offers almost unprecedented levels of defence industrial cooperation.

At the same time, it is unsurprising because the three parties are strong historical allies and part of the wider Anglospheric intelligence system. Strengthening their relationship is probably the most obvious step the US and UK could take to deepen their regional presence.

Advertisement

But Aukus is interesting not just for what it entails and which countries are included, but also for which countries are excluded. The agreement deepens existing relationships and diversifies the alliance system in the Indo-Pacific, but by focusing on three countries it also shuts out other key European and Anglophonic countries.

Meanwhile, the development of Aukus is a clear sign of America’s intent to balance China’s growing military capability through its regional alliances. It highlights how China’s policies towards regional states might have alienated Beijing and undermined the country’s position in the Indo-Pacific.

Aukus will focus in the immediate term on the development of nuclear-powered submarines for Australia, with an 18-month collaborative programme to determine the best way to deliver them to Canberra.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x