Advertisement

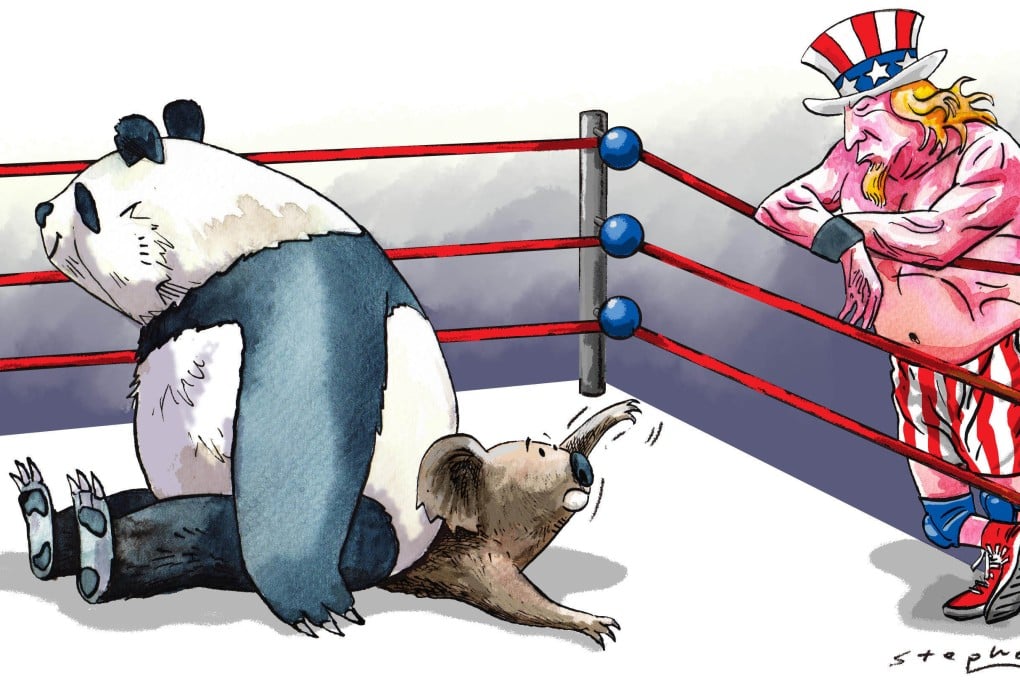

Opinion | As China-Australia trade tensions rise, will the US remain a bystander?

- The debate over the renewal of a Chinese company’s lease on the port of Darwin could be a litmus test of competing approaches to China in Australia

- Canberra is still looking for ideas on how allies can help each other when targeted economically by Beijing. So far, the US has offered little help on that front

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

51

Could Australia’s relations with China, already at their lowest point in decades, get any worse? The best place to answer this question is the port of Darwin in the scarcely populated north of the country.

Australia is reviewing the 99-year lease on the port signed by Shandong Landbridge Group in 2015 and approved at the time by regulators overseeing foreign investment. Security concerns about a Chinese company owning the access point to northern Australia were dismissed and even faintly ridiculed.

“If [ship] movements are the issue, I can sit at the fish and chip shop on the wharf at the moment in Darwin and watch ships come and go, regardless of who owns it,” Mark Binskin, chief of the Defence Force at the time, told a 2015 Senate hearing.

Advertisement

Since then, bilateral relations have been turned upside down. The two countries have fallen out over a series of disputes, ranging from Covid-19 to Huawei.

Beijing has implemented trade sanctions against billions of dollars’ worth of Australian exports. Australia, in turn, has drawn closer to the United States, including increasing troop rotations through Darwin to nearby training facilities.

No one is making lighthearted quips about fish and chip shops any more. Everything to do with China in Australia now passes through a national security lens, mirroring how such issues have long been dealt with in China itself.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x