Advertisement

Opinion | China doesn’t have a housing bubble. Here’s why

- China needs a large and vibrant real-estate sector to build enough housing in its big cities to meet the urbanisation demand in the next 10-20 years

- Its high levels of savings and investment should also be seen as a blessing, especially given the costly necessary transition to clean energy

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

11

In a recent New York Times article, Paul Krugman suggested that China’s economy could stagnate because of its unsustainably high level of savings and housing bubble. His prescription is that “China really needs to change its economic mix – to save less and consume more.” Both the diagnosis and prescription are very misleading.

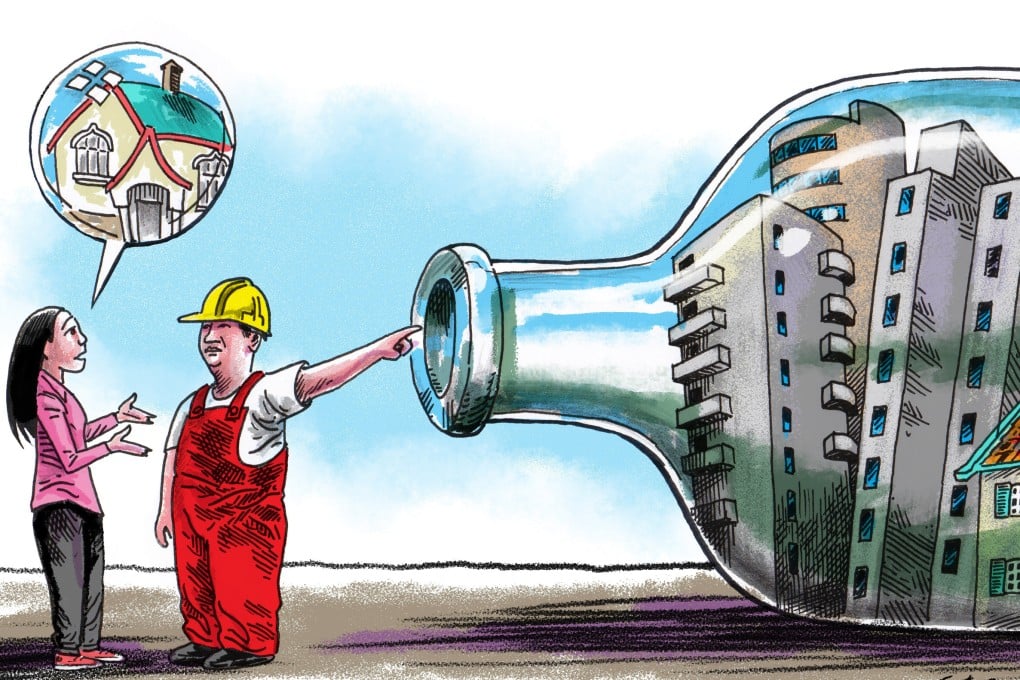

China has a large real estate sector and housing prices are high compared to other economies. But Krugman jumps to the conclusion that this constitutes a bubble. However, the high housing prices in large Chinese cities are not signs of speculative demand but, rather, a reflection of the supply shortage relative to real housing demand.

Per capita living space in large Chinese cities is small and new housing supply is well short of demand from young people wishing to live in these cities. Every year, millions of university graduates move into major cities to work, but struggle to afford housing. Moreover, there are hundreds of millions of migrant workers, most of whom can only afford to live in dormitory-type housing.

Advertisement

In the next 10-20 years, there will still be massive demand for urban housing and infrastructure investment in these large cities. China’s urbanisation rate is only about 60 per cent, some 20 percentage points below other typical middle-income economies such as Mexico (79.58 per cent) and Malaysia (74.84 per cent). Another 300 million people are expected to move into cities, especially large cities.

Over the next 20 years that would mean roughly 15 million people potentially moving into cities every year, with each person requiring US$200,000 of investment in housing and urban infrastructure on average, which works out to US$3 trillion a year, or 20 per cent of China’s current gross domestic product.

China’s biggest social problem is its urban-rural divide, particularly the hundreds of millions of migrant workers living in its big cities who cannot enjoy the social benefits urban residents do. The only long-term solution for this resident-migrant divide is to help migrant workers relocate to cities with their dependents, so they and their children will no longer be considered migrants.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x