Advertisement

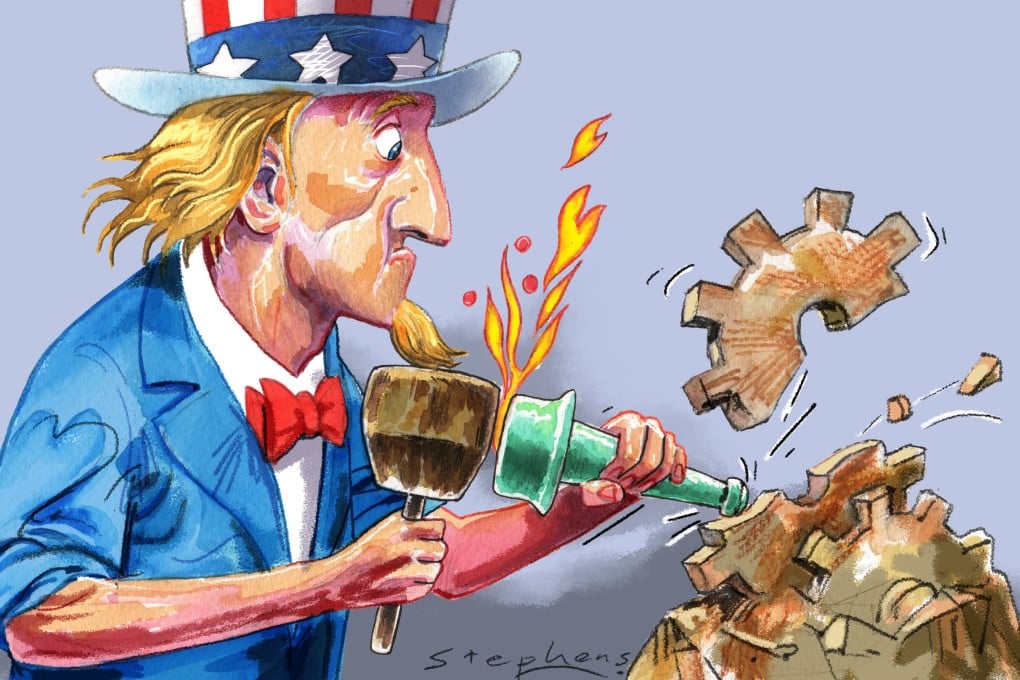

Opinion | Could a democracy like the US have crafted the ‘one country, two systems’ policy? Unlikely

- Managing the reintegration of Hong Kong with the motherland requires leadership of the highest order and a culturally advanced society

- The short-term cycle of elected governments in a democracy makes it virtually impossible for a policy like one country, two systems to gain traction

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

99+

Britain and China began negotiations over the future of Hong Kong in 1982. This was a “democracy” speaking to an “autocracy”, seeking to reach the near-impossibility of a consensus. In the Western world view, there could only be confrontation and contest to see who would ultimately come out on top.

Assume that, at the time, China had a different governing system – a democracy akin to the US model. Could the Joint Declaration, signed in 1984 as the product of those negotiations, have come about? It seems most unlikely.

Consider what was at stake. As the preamble to the Basic Law says: “Hong Kong has been part of the territory of China since ancient times; it was occupied by Britain after the Opium War of 1840.” The recovery of Hong Kong fulfilled “the long-cherished common aspiration of the Chinese people”.

Advertisement

China’s humiliation since the first Opium War has sunk deep into the Chinese consciousness. That war and its outcome led to the carving up of China. After Britain, other nations came along and each took a slice of the motherland.

The aim of the talks commencing in 1982 was for China to recover Hong Kong and redress historic wrongs, but what does “recover Hong Kong” mean?

In popular parlance, it would have meant just that – the total integration of Hong Kong back into the mainland. The system and policies as applied on the mainland were those laid down by the central government for the whole country. The average person on the street might have asked, “Why should they not apply equally to Hong Kong after reunification?”

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x