Advertisement

Opinion | China needs a new Zhou Enlai to revive foreign policy in era of US competition

- Persistent debate in other countries over China’s intentions shows its foreign policy is unclear and incoherent, leaving it open to attack

- A new approach that allows for foreign policy goals based on real perception and needs for China and other state actors is essential

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

19

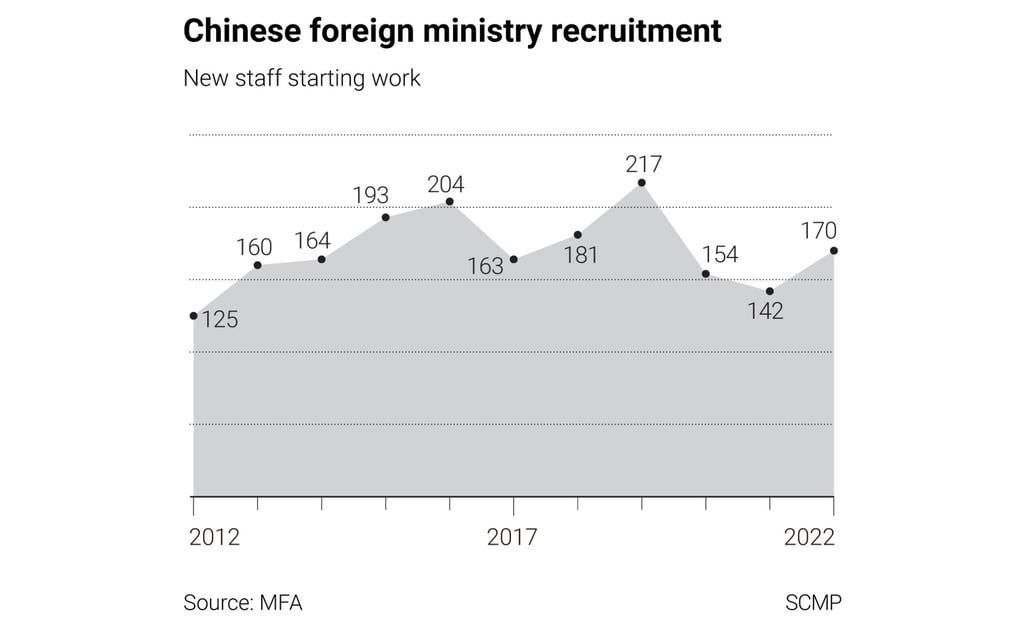

“China’s investment in diplomacy falls, as its global ambitions rise”, the Post reported on December 12. However, a reduction in China’s diplomatic resources is not the sole or even main challenge for China’s foreign policy.

An increase in diplomatic resources alone will not solve the challenges facing China, whether from increasing competition with the United States, growing suspicion from the West in general or increasing scrutiny facing the Belt and Road Initiative.

The real crux of the matter is for China to find a pragmatic foreign policy that balances the need to allay concerns of other countries and at the same time secure China’s interests. At present, certain actions by China might secure its short-term goals but at the cost of potentially creating a more antagonistic long-term international environment to China.

Advertisement

For example, the more aggressive “wolf warrior” diplomacy has not only ruffled feathers abroad but provided a justification for Washington to label Beijing the new threat to the liberal democratic world. Another would be the growing scope of bans by Washington on technological transfer to China as the US fears such technology will be used to further authoritarianism in China and globally.

In particular, there is a debate among US international relations scholars and policymakers about China’s foreign policy intentions. The question is whether it is a Leninist revisionist power, aiming to overturn liberal democratic international norms, or a defensive power striving to protect its political system from external intervention.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x