Advertisement

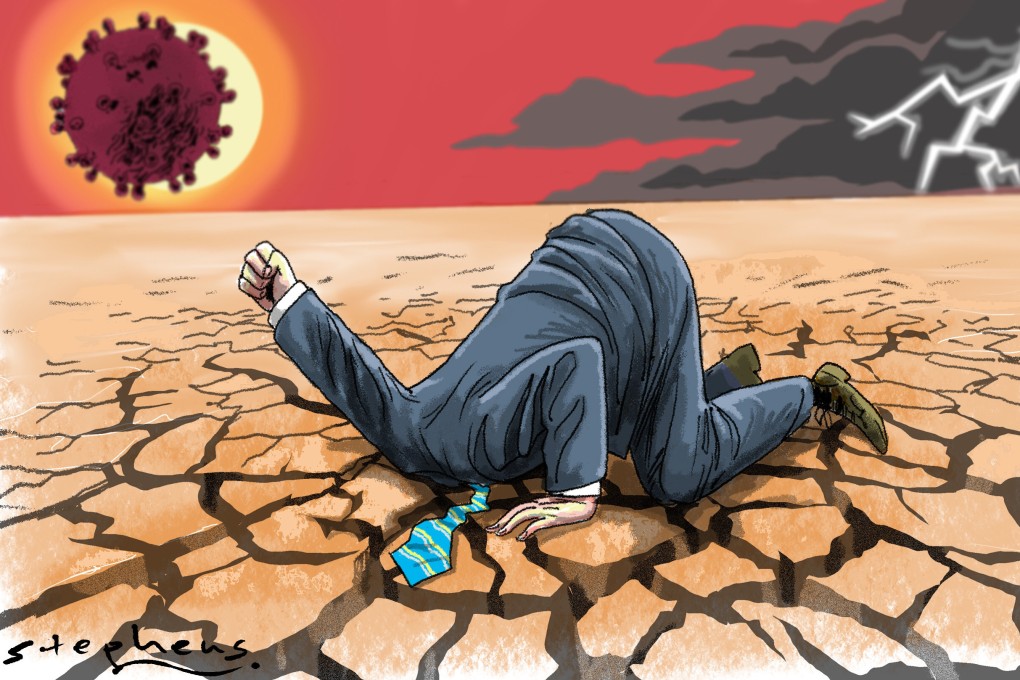

Opinion | Climate change and the pandemic loom large as world leaders obsess over politics and power

- The shortcomings in the global response to Covid-19 and climate change are illustrative of how the profit motive has blunted the human imperative

- Instead of joining forces against existential threats, leaders are focused on geopolitical competition and securing political power

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

2

The received wisdom of 2021 is that, in the larger global context, the Covid-19 pandemic and climate change will be the biggest challenges to human security. The numbers tell their own story.

At the end of 2021, global cases of Covid-19 were estimated at around 292 million with almost 5.5 million deaths. This translates to almost 700 deaths per million among the global population.

With the emergence of the rapidly transmissible Omicron variant, the number of daily global cases has surpassed 1.5 million and is still increasing. While there is agreement among experts that the new variant appears to be relatively mild, there is still the reasonable chance that the coming year could bring a more lethal mutation and a subsequent spike in the global death toll.

Advertisement

Climate change had disastrous effects across the globe in 2021. Images of floods and unseasonal weather patterns punctuated a blighted year. A preliminary report by the NGO Christian Aid estimated that each of the year’s 10 mostly costly natural disasters crossed the US$1.5 billion mark, with Hurricane Ida in the United States topping the list at US$65 billion in damage.

Two of the top 10 events – Cyclones Yaas and Tauktae – took place in India. While their costs have been estimated, their overall impact on the country’s large population has yet to be accurately determined.

This tragic pattern permeates the developing world. Those at the lower end of the socioeconomic ladder are the worst hit by climate change while the sources of the ecological degradation leading to climate change lie with the world’s rich and powerful.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x