Advertisement

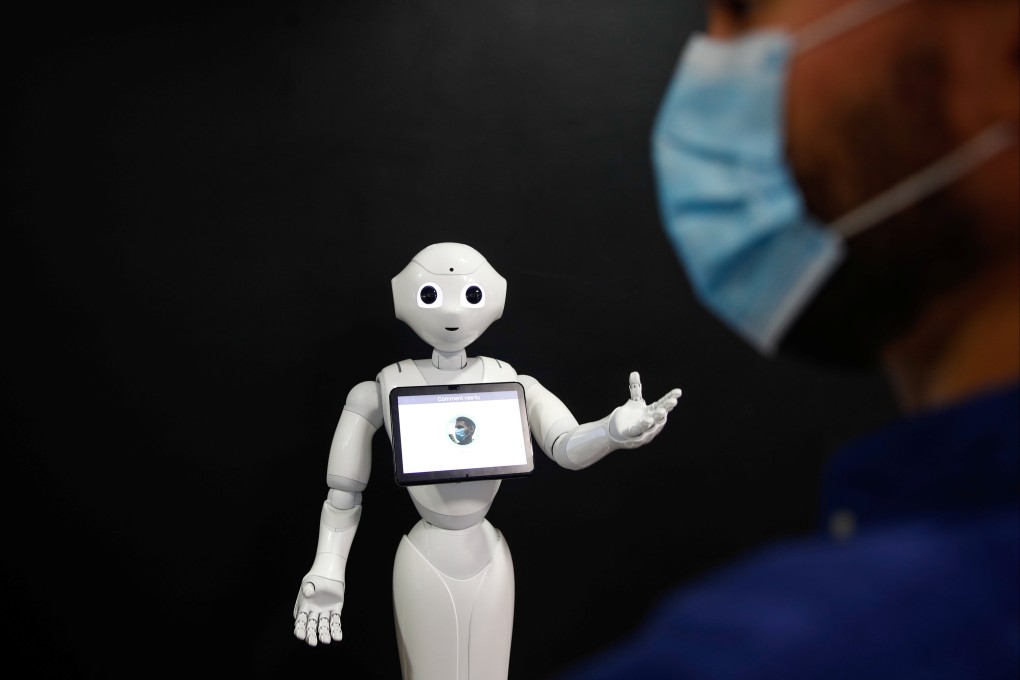

Opinion | Robots are helping us fight Covid-19, but can we learn to love them?

- From taking swab tests to reminding people to wear a mask, service robots have been indispensable to global efforts to end the coronavirus pandemic

- Yet, given the unease many people still feel towards robots, the next stage of development will focus on making them more friendly rather than more functional

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

1

Back in April 2020, during the first coronavirus outbreak in Hong Kong, disinfection robots developed in the city were deployed at the airport to help fight Covid-19. Today, as we face the risk of a fifth wave of infections, service robots are becoming more common. The issue that we now need to consider to make these robots more effective is the emotional reaction people have towards them.

First, let’s look at how service robots have been used during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Essentially, robots are machines programmed by humans to perform an intended task. While years ago, robots were used primarily in industrial automation (e.g. welding and assembly robots), today they are being deployed in the service sector to perform useful tasks for humans.

Advertisement

Depending on the application field, service robots can be further categorised as personal service robots (e.g. domestic servant robots) or professional service robots (e.g. firefighting robots and surgical robots).

The highly contagious nature of Covid-19 has accelerated the development and adoption of professional service robots, especially in areas that require human contact, such as delivery, cleaning and medical care.

According to a global comparison conducted by robotics scientists, China ranks in second place for instances of robot use in tackling Covid-19, as well as the technical readiness of its robots.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x