Advertisement

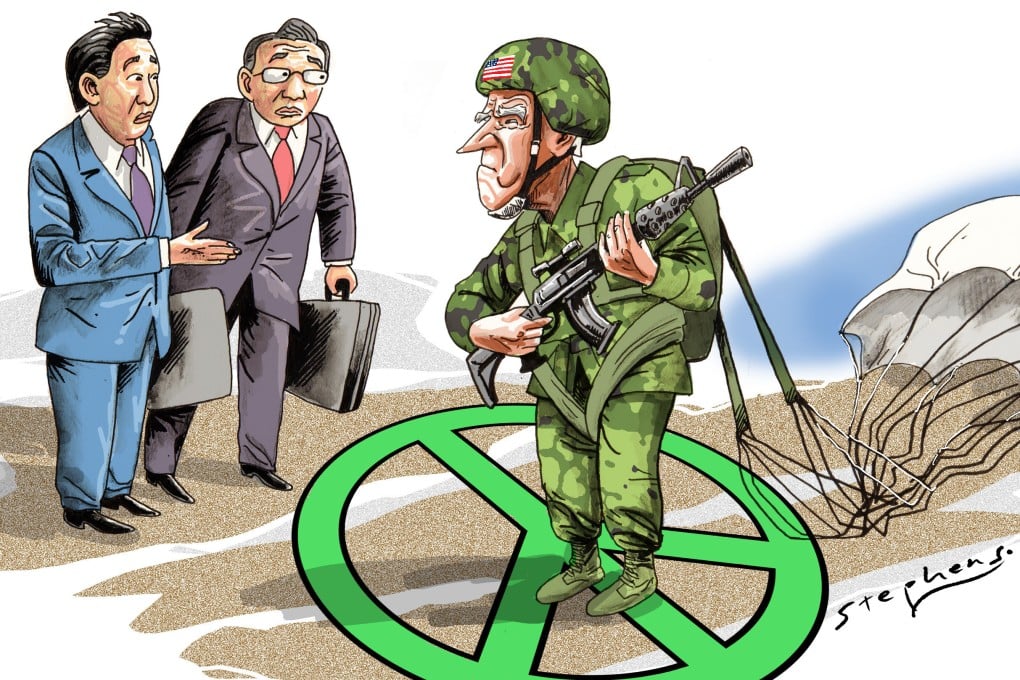

Opinion | How a belligerent US is forcing conflict on East Asia

- The US is prioritising military approaches over economics, which jars with a region deeply invested in peace, stability and prosperity

- This crisis demands thinking and acting outside the box of political expediency, but there is little sign the US is capable of doing so

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

39

A pandemic, trade war and crimps on global supply chains or not, East Asia is still humming. The region remains the world’s most vibrant economic space. It was the case before Covid-19 and Trumpism, and it will be in the future.

The United States and Europe are major economic stakeholders in East Asia without being part of it. But will Washington further risk its considerable stake with more political posturing?

The 15-member Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, initiated by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, took effect on January 1 with China at the centre of the world’s largest trade bloc. China has also formally applied to join the 11-member Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, the successor to the Trans-Pacific Partnership which the US led before quitting under former president Donald Trump.

Advertisement

These groupings complement existing trade pacts between China and its regional partners. But US President Joe Biden’s “new economic framework” is conspicuous by its absence after more than a year of his administration.

Washington’s latest approach is an alliance of democracies to compete against China. There are doubts over that prospect while greater strides are evident in politico-military initiatives such as the Quad and the Aukus agreement.

Prioritising military approaches over economics jars with a region invested in peace, stability and prosperity. East Asia’s business is business, with a collective repudiation of conflict regardless of cause or justification.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x