How Hong Kong can become an environmentally responsible, carbon-neutral city

- Hong Kong should revolutionise its building codes, to enable owners and developers to innovate

- Beyond that, we should be investing 2 per cent of our annual GDP to achieve a net-zero carbon economy, generating returns from green initiatives to attract developers and investors

The idea of environmental consciousness has been around for the past four decades since the World Commission on Environment and Development introduced the concept of “sustainability” in 1987. Thirty-five years later, the world is still tiptoeing around creating environmentally friendly societies.

The challenge always hinges on the state of social development and available resources. Developing countries’ highest priorities are providing food, clean water and reliable transport and civic infrastructure, much less worrying about being sustainable.

For developed countries, transformation often involves doing away with the old. Stakeholders need to justify the value in destroying what is already functional and profitable.

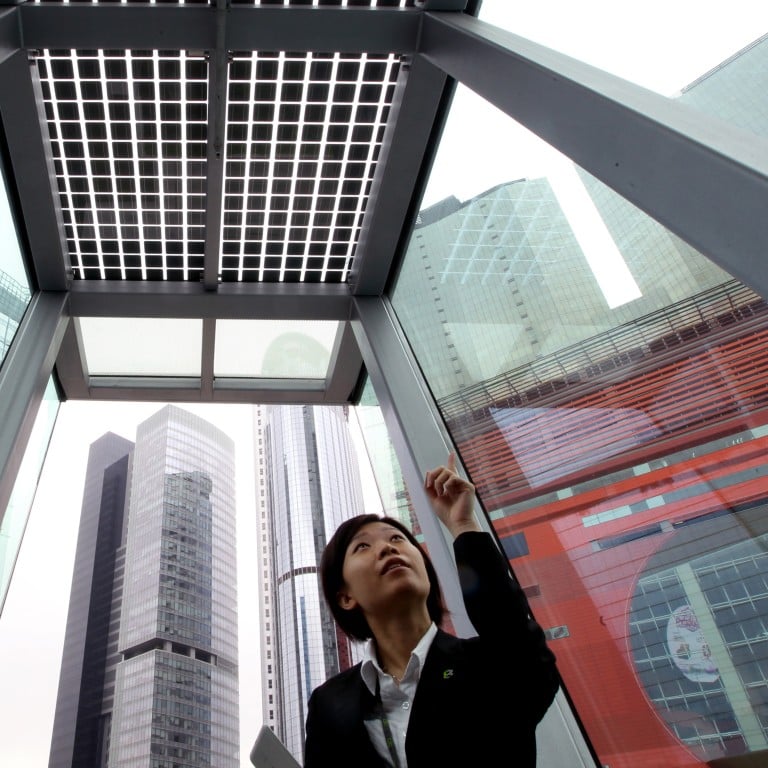

How can we start making significant environmental positive impacts? We need to look no further than what Hong Kong is made of: countless residential and commercial towers that define our skyline and fill our urban core.

Buildings account for about 28 per cent of operational carbon emissions and 11 per cent of embodied carbon emissions, totalling close to 40 per cent of global energy-related carbon emissions, according to the World Green Building Council. If we can build responsibly, we can take huge steps in achieving a carbon-neutral society.

Last April, the Hong Kong Green Building Council (HKGBC) organised the Advancing Net Zero Ideas Competition, with real project sites and objectives and calling for architects, engineers and professionals to contribute viable and visionary ideas in achieving carbon neutrality in buildings.

Unlike most conventional design competitions, the award ceremony and exhibition of entries were not the end of the quest.

Can longer property leases help reduce pollution?

The competition – largely unknown to the general public – represents a giant step in the right direction that benefits society as a whole.

Our current building codes date back several decades with minor revisions over the years. There have been baby steps but no overhaul in catching up to today’s development needs and the technology available to streamline design and construction.

While commerce should not see the guardian as the enemy and understands its job to be sceptical of new ideas and standards, the guardian should be open-minded to recognise positive effects of innovations that improve public safety and the common good.

The keyword is “invest”. This means the amount is not a giveaway but would generate returns from green initiatives, which should attract developers and investors. How much is 2 per cent of Hong Kong’s annual GDP? We are talking about HK$53 billion (US$6.8 billion) annually, a substantial amount but certainly manageable if collectively supported by the makers of Hong Kong.

The real cost, other than investments, would be a collaborative and empathetic spirit. Perhaps for the first time, the Hong Kong government – with strong backing from the central government – could round up influential developers to achieve a common goal beyond profits and shareholders’ interests.

Dennis Lee is a Hong Kong-born, America-licensed architect with 22 years of design experience in the US and China