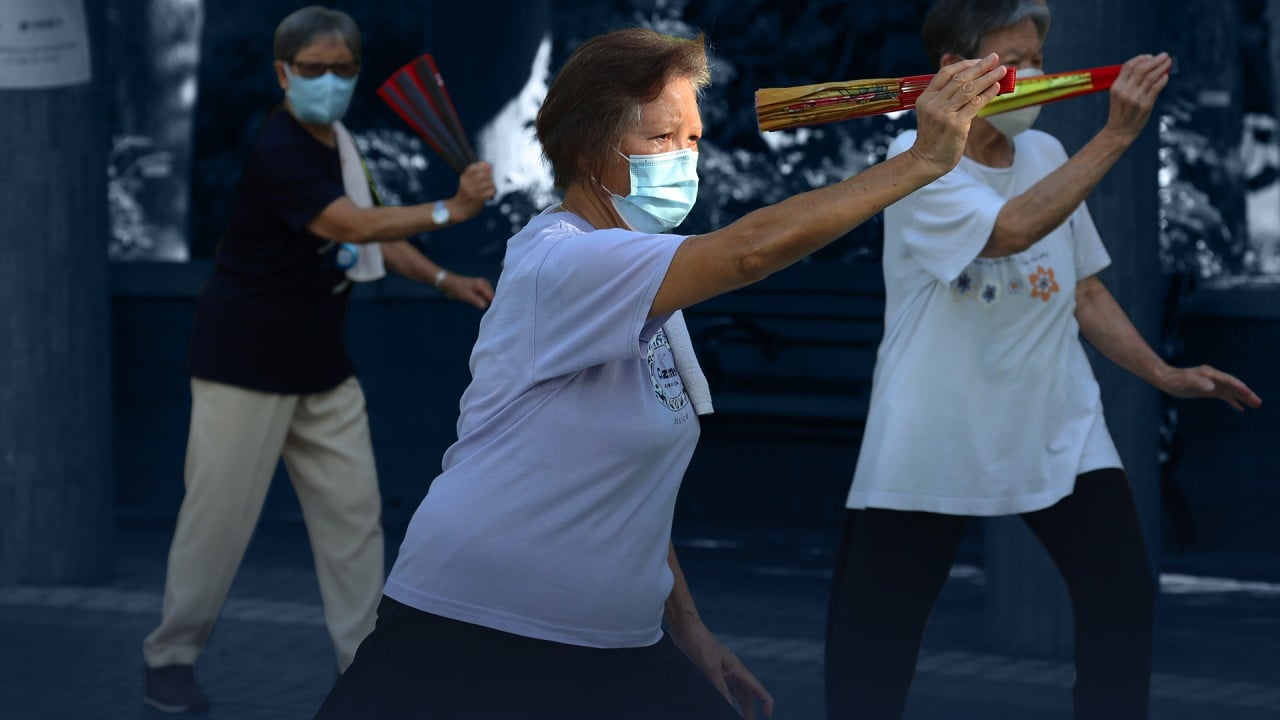

Hongkongers are living longer but not healthier as ageing population puts extra burden on health care

- Chronic diseases, disabilities and dementia are on the rise among Hong Kong’s ageing population while the pandemic has further exposed the lack of resources in elderly care

- The city has the financial means and central government support to do better, but it has focused on treatment over prevention

Among the elderly population aged 65 or above, the proportion aged 85 or over has risen from 5 per cent in 1981 to 16 per cent in 2021. This is expected to surpass 30 per cent by 2066, which means one in every three elderly people will be 85 or above.

Furthermore, the number of people aged 100 or above has increased from 289 in 1981 to 11,575 in 2021, which is an alarming rise over the past 40 years. The number of centenarians in Hong Kong is expected to continue increasing. Have we made sufficient preparations for the scale of this challenge?

One of the biggest problems that needs to be addressed with an ageing population is their growing health care and welfare needs. According to the World Health Organization, the prevalence of people diagnosed with cancer, chronic cardiovascular disease and dementia increases with age.

New research by Hong Kong Shue Yan University shows that more than 80 per cent of our elderly have difficulty walking, or require the support of others or the use of assistive equipment to walk. Nearly 85 per cent have one or more chronic diseases, such as high blood pressure and heart disease.

At present, more than 8 per cent of the elderly population in Hong Kong live in residential care homes, which is higher than that in Japan. A sustainable and humane policy for elderly care is a necessity.

Thus, the responsibility for responding to emotional problems among the elderly in residential care homes has fallen on the medical staff.

An increase in cases of suicide among older adults with confirmed cases of Covid-19 over the past two weeks is a wake-up call to pay more attention to mental health during the pandemic.

With advances in medical technology, the gap between longevity and good health has widened. We are living longer but not healthier.

Health is not merely the absence of disease but a multidimensional and dynamic interaction. It includes the physical, cognitive, functional, spiritual and psychological aspects, social engagement and family support, as well as an individual’s adaptability and resilience, self-regulation and a stable source of income and financial security to respond to evolving challenges.

Unfortunately, Hong Kong has leaned more on treatment than prevention. There is much to be learned from studies on centenarians, and the protective factors which can help them live a healthy and long life provide a blueprint for health care and disease prevention.

Paul Yip is a chair professor (population health) in the Department of Social Work and Social Administration at the University of Hong Kong. Dr Karen Cheung is Centre on Ageing Fellow in the Sau Po Centre on Ageing at HKU