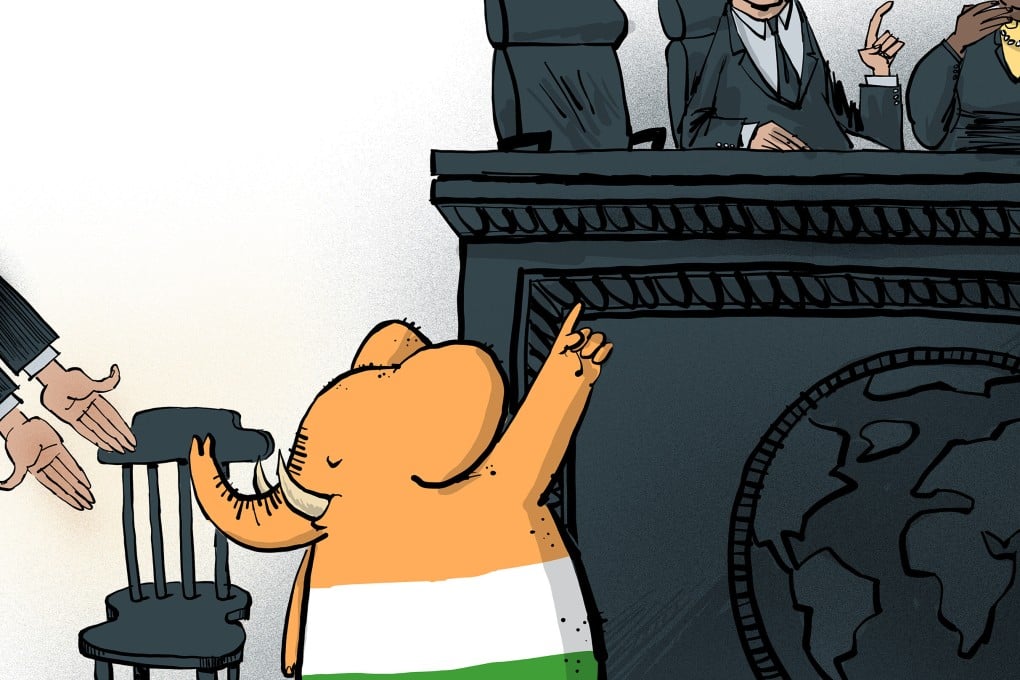

Opinion | India’s reasons for not joining West on Ukraine go beyond economics and arms deals

- India’s imports of Russian arms, fertiliser, fossil fuels and more only partly explain why it has not joined the West’s sanctions against Russia

- India has feet in both the global south and the Western alliance, and it has a vision of a multipolar world where it does not kowtow to any great power

University of Chicago professor and author John Mearsheimer has drawn heavy criticism for his analysis of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. His argument that the war in Ukraine was the West’s fault because it supported states that neighboured Russia and expanded Nato has come under fire from many analysts in the Western world and unleashed a fresh wave of criticism of his body of work across traditional and social media.

Interestingly, his analysis is respected in India. The Indian administration under Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been no different from its predecessors in adopting a realist foreign policy that puts its own economic and political interests over any moral arguments of right and wrong in foreign affairs. The conflict in Ukraine is no exception.

India’s position on Russia is not new and is unlikely to change any time soon. This has to do with macroeconomics and its multipolar vision for the world.

With the price of crude touching levels close to US$130 per barrel, it made economic sense when Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman said in response to buying Russian oil, “We have received quite a number of barrels, I would think three to four days’ supplies and this will continue” and “India’s overall interest is what is kept in mind”.

In addition, around 50 per cent of India’s defence imports are of Russian origin. India’s dependence on Russia for supplying and maintaining its military makes antagonising Moscow out of the question.