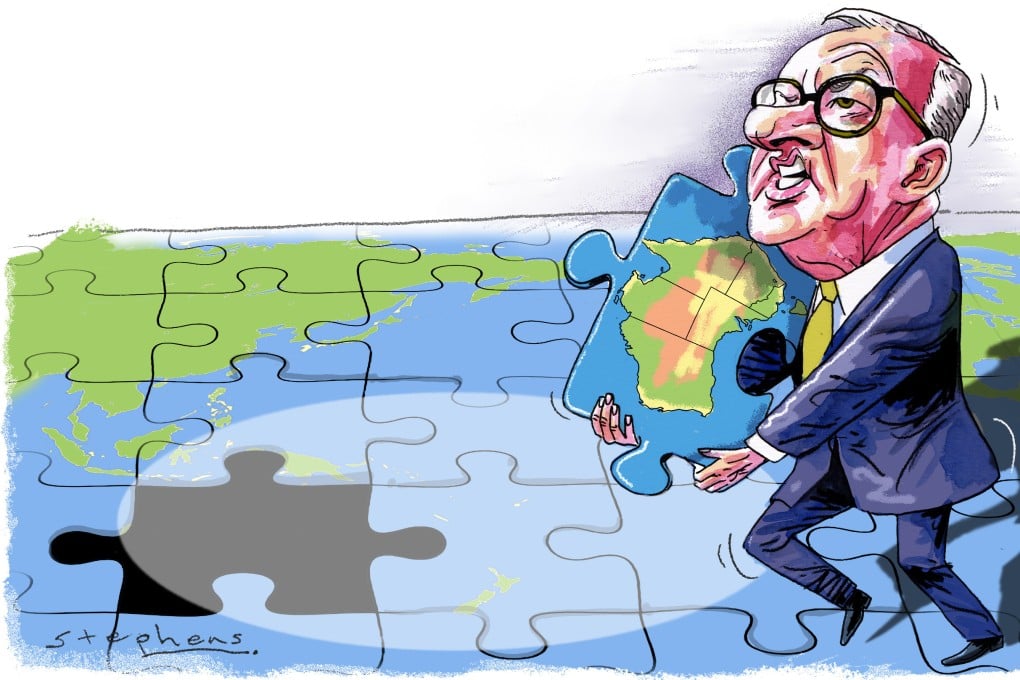

Opinion | Under Labor leadership, Australia has a chance to end its foreign policy incoherence

- With Aukus and the Quad, Australia’s capability to engage, at least on security matters, with democracies in the region has grown. However, this has not played into a larger vision of Australia’s place in the region

- Whether on the Pacific or China, Australia’s foreign policy needs clarity and coherence

For almost a decade, Australia has been governed by the conservative Liberal-National Coalition, which undoubtedly led the nation through profound domestic and regional turbulence. Yet, rather than emerge with a renewed sense of ambition or self-assurance on the world stage, Australia’s foreign policy has consistently exhibited incoherence and uncertainty.

Indeed Penny Wong, Australia’s new foreign minister, has acknowledged this in the past, stating that, “Our nation has not known such a vexing convergence of circumstances since World War II”.

Yet there is a difference between recognising change and responding to it. With a new progressive government under the Labor Party taking over, Australia has a crucial opening to rejuvenate its position on the world stage.