How China’s belt and road diplomacy could end the Ukraine conflict for good

- Ukraine’s integration into the ambitious rail network linking China with Europe, by providing alternative routes bypassing Russia, would be acceptable to the EU and US

- And Russia, too, could be open to China taking a lead on brokering a sustainable ceasefire, especially if it means lifting some sanctions

A post-war scenario in Ukraine that favours both Russian and Western interests is key to a sustainable ceasefire. China could be well placed to pitch its Belt and Road Initiative as the key road map to this scenario.

China’s dislike of unilateralism gave rise to a Sino-Russian diplomatic partnership that has seen the two permanent UN Security Council members oppose US military intervention in Syria, sanctions on Iran and other similar policies.

However, Russia’s February 24 invasion of Ukraine was a unilateral move itself, and its impact on China’s global interests shows why Beijing opposes unilateralism.

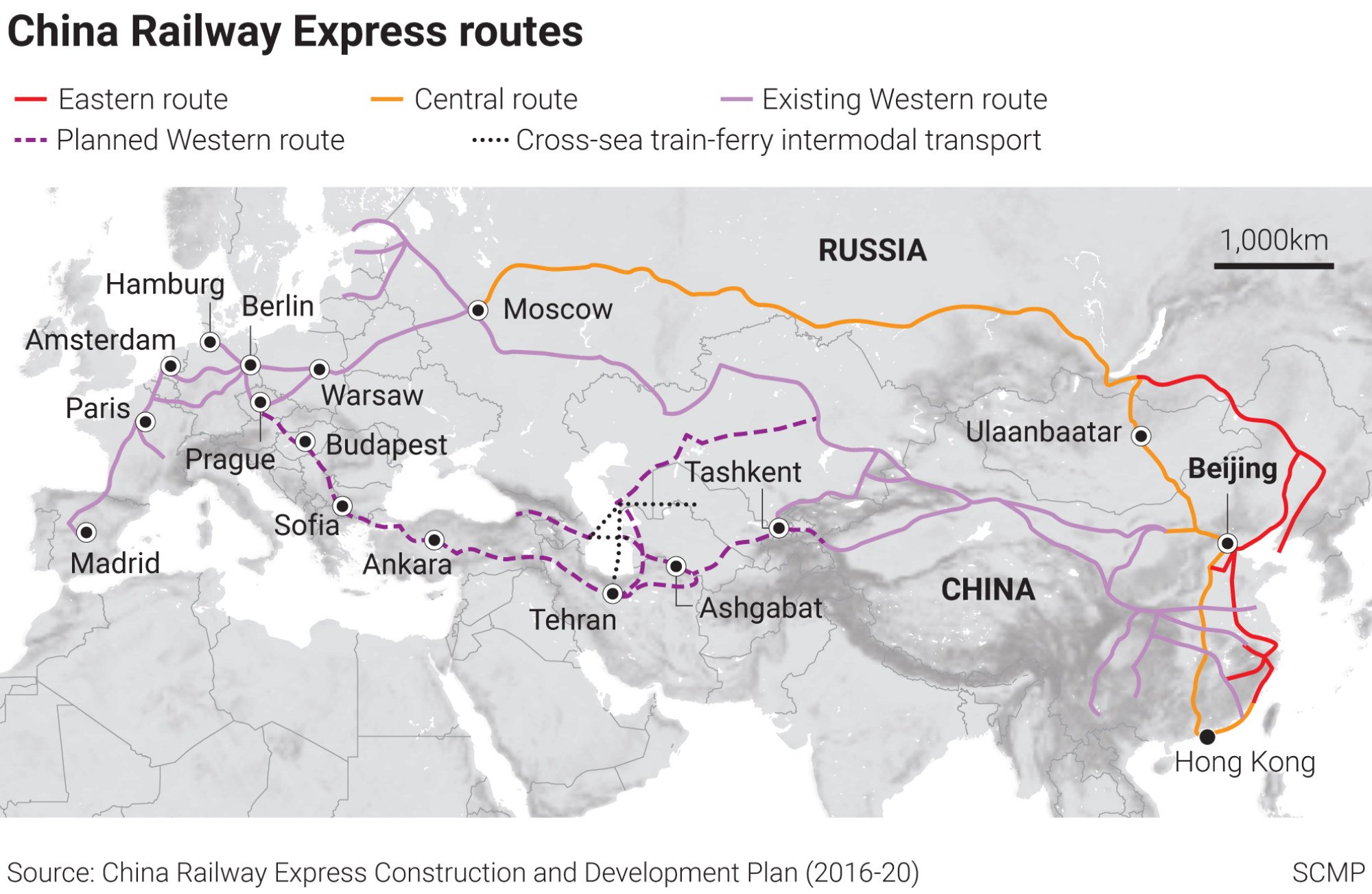

Russia’s unilateral invasion torpedoed these plans and also invited unprecedented European Union sanctions on Russia. This has affected China’s trade with Europe, most of which transits the Russia-Belarus part of the belt and road’s “New Eurasian Land Bridge”. As a result, China retains a strong interest in getting both Russia and the West to back off in Ukraine.

Usually, China avoids the diplomatic entanglements that accompany foreign conflicts as much as it avoids the conflicts themselves. However, Beijing possesses credible neutrality on Ukraine, and the geopolitical outcomes of Ukrainian integration into the belt and road may be acceptable enough to both Russia and the West for them to de-escalate at China’s urging – so as to allow Ukraine’s belt-and-road-driven restoration – without looking like they capitulated.

Ukraine’s integration involves heading an alternative China-EU trade route to the Russia-Belarus one. This multimodal route, dubbed by some as the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, proceeds from China to Kazakhstan then crosses the Caspian Sea to Azerbaijan and neighbouring Georgia en route to the Black Sea, to Ukraine’s ports. Ukraine then serves as China’s entrepot to Europe.

‘Hell on earth’: can the world spend its way out of the global food crisis?

From Russia’s perspective, while it may lose economic hard power in the event of a Chinese-led ceasefire in Ukraine and development of the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, it would benefit in other ways from China developing deeper stakes in resolving the Ukraine conflict.

After a ceasefire, the next logical step in China’s belt and road diplomacy would be to renew multilateral dialogue on Ukraine to finalise some semblance of Russian-Western – or at least Russian-EU – common ground and end the conflict for good. Such a dialogue would undoubtedly reflect China’s general rejection of Western sanctions on Russia; hence, the restrictions would need to be lifted as a prerequisite.

This would spare Moscow from having to bargain for sanctions relief by conceding to Western demands, like vacating occupied Ukrainian territory, which would damage Russian credibility as a hegemon in the former Soviet space, which it calls its “near abroad”.

US sanctions pressure on Russia shows geopolitics now trumps economics

A close look at China’s interests in Ukraine shows they complement US, EU and Russian interests in different ways. All these key players in the Ukraine crisis can claim some strategic gain from a Chinese-led ceasefire reached under the pretext of letting Ukraine embrace the belt and road.

For China, the ceasefire itself would be a special achievement. So far, the Ukraine war’s destabilisation of vital global markets, including food and energy, has not been enough to convince Russia and the West to wind down their posturing. Such an outcome would burnish the belt and road’s global reputation as a megaproject rooted in “win-win cooperation”, as Beijing markets it.

What is certain is that everyone needs a ceasefire in Ukraine. China has the motive and means to lead efforts to this end.

Agha Hussain is an independent geopolitical analyst in Rawalpindi with a special focus on Eurasian affairs