My Take | Why a committed ruling elite is essential to economic development

- A new book offers a realistic look at how developing countries can succeed in achieving wealth and stability

Every few years, a book on development economics gets everyone talking. I have bought my share of them over the years, but not necessarily for my enlightenment. Their theses tend to cancel each other out, and I ended up more confused than before.

In the mid-2000s, economist Jeffrey Sachs released The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time, arguing that foreign aid, judiciously applied, can help poor countries overcome the interlinked problems of extreme poverty, low or zero growth and environmental degradation.

A few years later came Dead Aid: Why Aid is Not Working and How There is a Better Way for Africa by former Goldman Sachs banker Dambisa Moyo, who criticised massive foreign, mostly Western aid, for achieving nothing over many decades other than perpetuating dependency, corruption, poor governance and poverty among recipient countries.

Moyo is particularly memorable to me, but not in a good way. She actually made me much poorer. But for reading her, I would have been richer by a few million, at least in Hong Kong dollars. I can’t remember whether it was this book or her subsequent one, How the West Was Lost, where she wrote that from an investment point of view, there ought to be no difference between putting your money in real estate or the stock market. Sure enough, I sold my flat in west Mid-Levels in 2010 and put most of the money in stocks. For those who know about the Hong Kong property market between 2006 (when I bought the flat) and now, you get the picture. I had to see a psychiatrist after that.

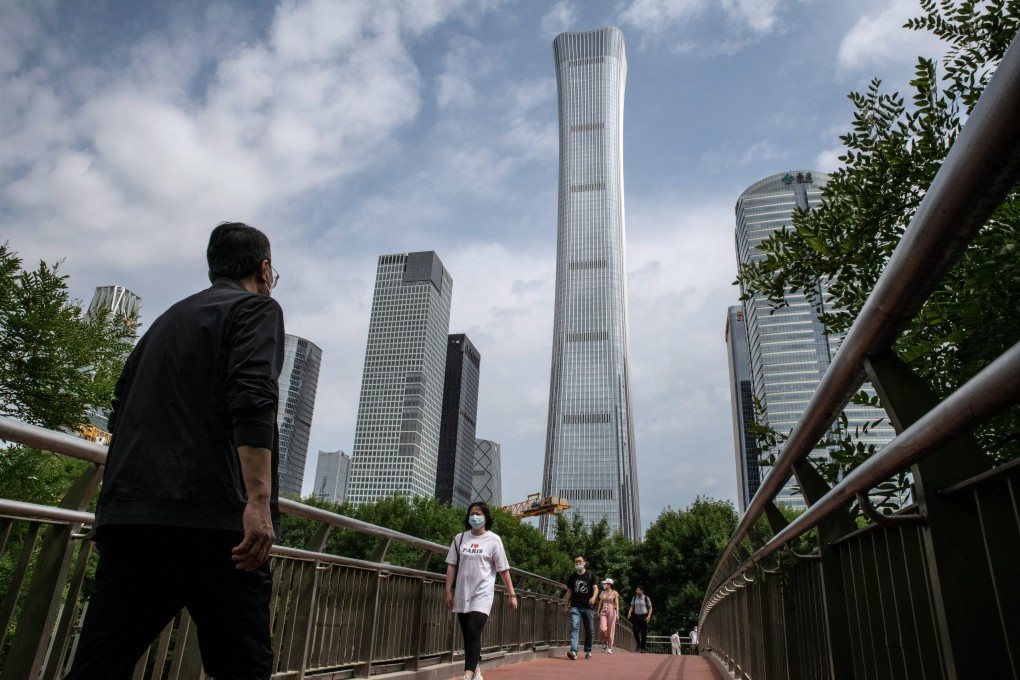

But sorry to digress. So, aid or no aid? For me, no idea. Then economists Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson made a splash with Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. To achieve sustainable growth and development, you need proper political and economic institutions such as inclusive democratic governance and intellectual property protection. Well, sure, but look at China!