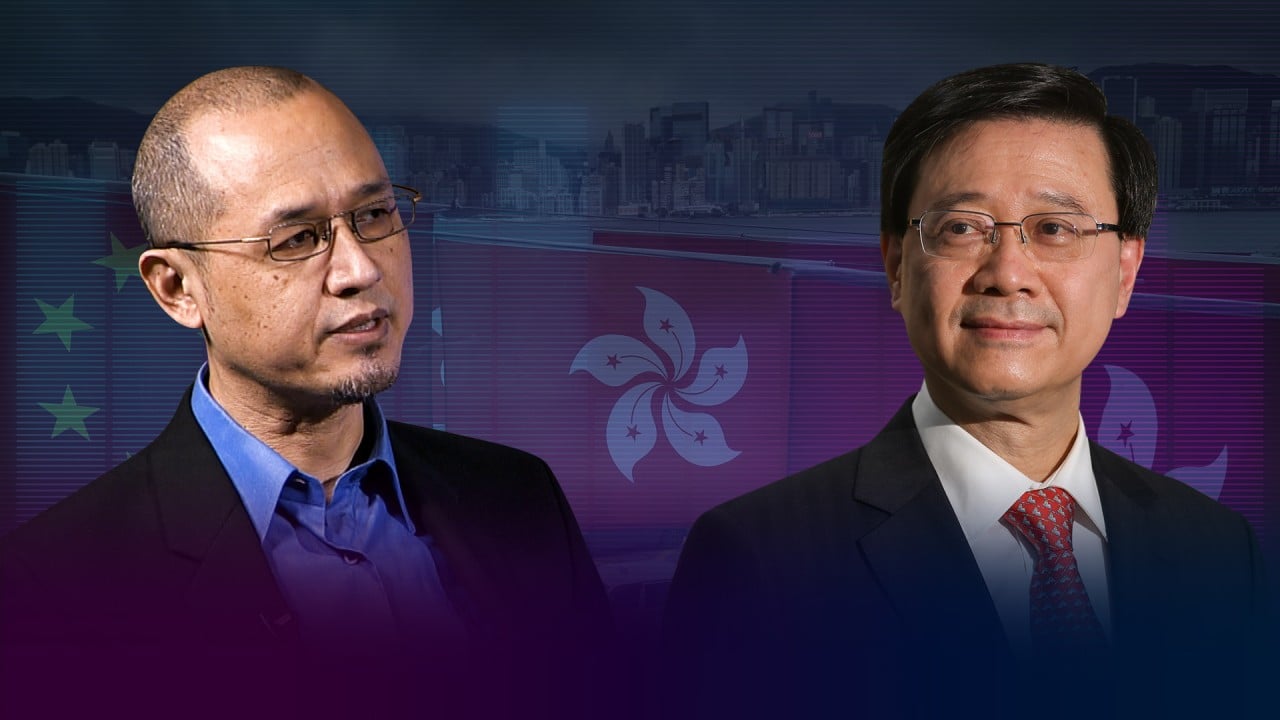

John Lee must assure the world Hong Kong’s freedoms aren’t lost

- Over the years, Beijing has become more hands-on in Hong Kong’s governance, and while the city has not won the democracy it sought, its freedoms must remain intact

- Hong Kong’s new chief executive needs to build confidence with action, not resort to propaganda

Writing 25 years ago in an American think-tank publication launched to chronicle the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region’s birth, I penned a report on its first month and noted that the Post had, on July 28, published the findings of an opinion survey in which confidence in the city’s economic and political future had risen by five points, to 98, since April 1997.

That optimism contrasted with the alarmist warnings being sounded by the Western media in the run-up to the handover.

The optimism proved justified. In the first five years and more, the Communist Party and Chinese government bent over backwards to give then chief executive Tung Chee-hwa, a man they trusted, a free hand in running the SAR.

But when Tung failed to enact national security legislation as Beijing expected (and as many in Hong Kong dreaded) in 2003, Beijing adopted a more hands-on approach, eventually including involvement in local politics.

Meanwhile, pro-democracy politicians demanded the introduction of universal suffrage elections. Before 1997, Lu Ping, director of the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, had repeatedly pledged that Hong Kong people, not Beijing, would decide when the Legislative Council would be elected by universal suffrage.

The degree of autonomy had narrowed, most likely because of the Article 23 fiasco.

From 2003-2004 onwards, Hong Kong-Beijing ties were increasingly brittle, with Hong Kong democrats demanding universal suffrage and Beijing adamantly insisting the time was not ripe. The SAR government, caught in the middle, tried not to offend either side.

Opinion surveys were a case in point. The central government’s liaison office put pressure on Robert Chung Ting-yiu, then director of the public opinion programme of the University of Hong Kong, to stop asking people about their sense of identity. Such surveys showed that, increasingly, more thought of themselves as Hongkongers than as Chinese.

Hong Kong not a ‘show flat for Western democracy, must win back Beijing’s trust’

In January 2012, Raymond Tam, the secretary for constitutional and mainland affairs, responded by endorsing academic freedom, specifically including the right to conduct surveys. But he also upheld the right of mainland officials to say whatever they liked because “freedom of speech and freedom of expression are Hong Kong’s core values”.

Critics say one country, two systems is finished. But the SAR, with its own currency, passport and membership in the World Trade Organization isn’t just another Chinese city. Still, the national security law has definitely changed Hong Kong. There’s no gainsaying the fact that rights and freedoms are affected.

Hong Kong opposition down and out, trying to find its place

It would be wonderful if the new chief executive turns into a champion of freedom. This is no joke. Lee is trusted by Beijing, just as Tung was. If Lee demonstrates through deeds that freedom continues, aside for narrow exceptions, he can reassure not only foreign businessmen but also the local population.

Of course, he will need Beijing’s backing. China’s agencies in the SAR must similarly respect freedoms, now that they can wield power directly in Hong Kong.

It is a tall order. But if Lee wants to revive Hong Kong with a reset that lures back foreigners, he needs to keep locals happy as well. Freedom is the bottom line. Democracy can be set as a future target but the requirement for freedom is immediate.

Frank Ching is a Hong Kong-based writer and commentator