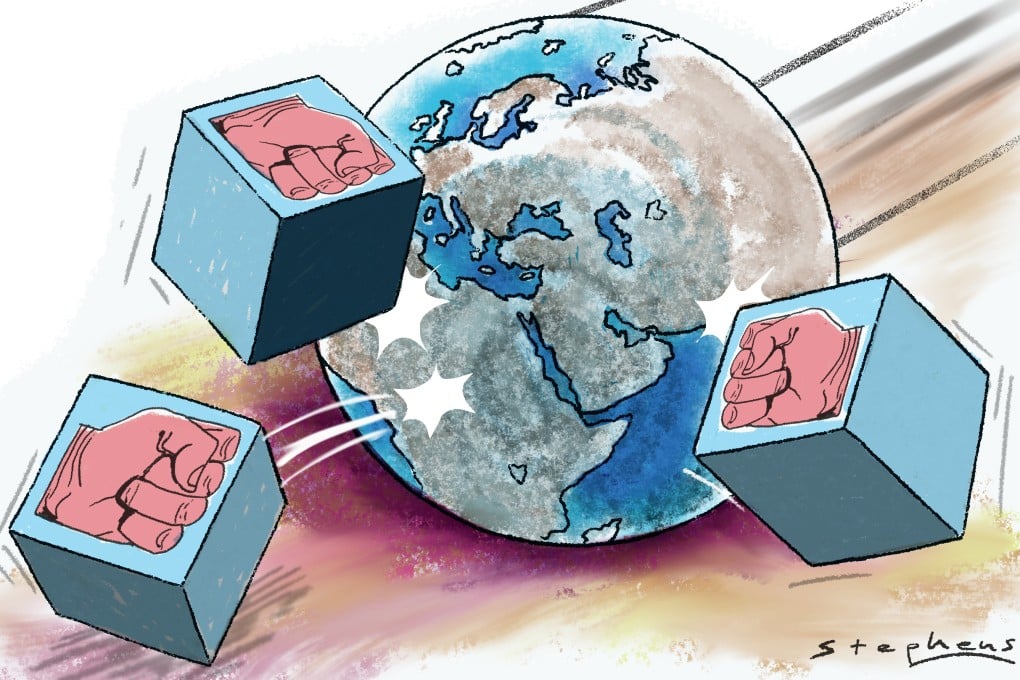

Opinion | Both G7 and BRICS lack the dominance to resurrect grand rivalries of Cold War power politics

- Back-to-back recent summits – one involving the US and its friends in the rich West, another featuring China and other emerging powers – have stoked talk of bloc-based confrontation

- In reality, a united front is an illusion for groupings like the EU, while emerging powers seeking a bigger say in the international system don’t wish to confront the US

Xi was joined virtually by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, South Africa President Cyril Ramaphosa, Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro, and Russian President Vladimir Putin. Facing a barrage of Western sanctions following his invasion of Ukraine, Putin welcomed the high-profile event as an opportunity to rally support from fellow emerging powers.

On the surface, the BRICS and G7 groupings seem to represent rival power blocs amid the intensifying Sino-US cold war. On closer examination, however, it’s clear that many emerging powers simply seek a bigger say in the international system rather than confrontation with Washington.

Meanwhile, many in the West are divided on how best to deal with newly risen powers, especially China, given the absence of direct geopolitical conflict and the depth of bilateral economic relations.