ESG financiers need to first practise what they preach on climate change and net zero

- Truly delivering net zero and combating social and environmental injustice requires mostly perspiration, which means that real people and companies have to deliver

- Financial wizards, meanwhile, can just claim they are doing their fair share by policing ESG

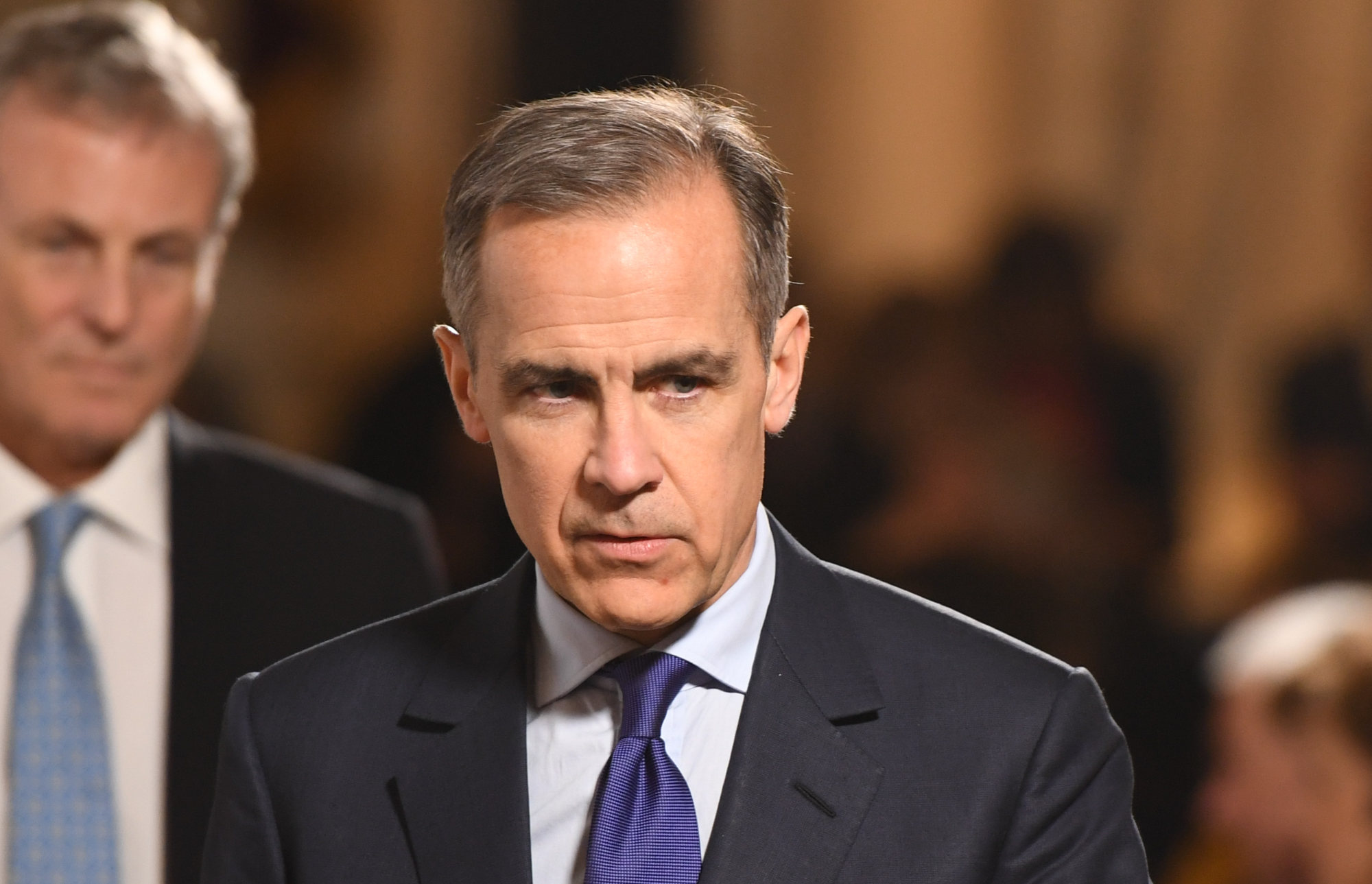

The model gained global attention in 2021 when the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), led by UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance Mark Carney, corralled 450 members representing US$130 trillion in assets to unite net-zero finance initiatives from across sectors and countries in one “industry-wide strategic alliance”.

In Carney’s words, “GFANZ is accelerating the best-practice tools and methodologies that are essential for ensuring that the climate is at the heart of every financial decision”.

As a vision, ESG looks impeccable, except one needs to ask – whose vision? Will ESG deliver net-zero results? And who will work hardest to deliver?

My immediate reaction when GFANZ was announced was: how did 450 institutions, mostly in advanced markets, with assets amounting to 1.3 times the global GDP, gain so much power?

If they really cared about net zero and ESG, how come it took so long to switch from short-term greed to long-term value? And if GFANZ will not lend to or invest in companies that do not meet ESG standards, isn’t it more a stick than a carrot?

Furthermore, I cringe whenever someone talks about best standards and practices, because the best standards for the financial sector may not be best for real-sector companies and borrowers.

Note that those who practised “best standards” were hit harder by the 2008 global financial crisis than those low-standard EMDEs which suffered the spillovers. The remedy for advanced economies and financial systems will not work for developing economies with less-sophisticated systems. Cancer medicine does not cure malaria.

After 40 years working in financial sector regulation, pushing “best standards” designed by the West, my experience is that the rest of the world would have preferred “best fit”.

When the multilateral banks and agencies insist on “best standards and practices”, their loan conditions became so complex and stringent that many EMDEs can neither meet them nor access the funds in a timely manner for their real needs.

Applying this concept to ESG, the environmental component can fill in for globalisation, given that we all live on one planet and are interconnected through financial, supply and cultural networks. How we consume and act affects other people and the planet. The social component relates to inclusivity and social justice, which is a matter of democracy.

Governance, then, is a sovereignty matter. And it is critical; without good governance at the individual, family, firm, city or state levels, there will be little social justice and bad consequences for the planet.

Developing world crying out for investment in sustainable infrastructure

In short, the “E” and “S” of ESG matter, but if we can’t get our domestic and global governance acts together, there will be terrible outcomes for people, profit and the planet.

The ESG initiative really came about when businesses realised that the drive for profit was hurting people and the planet in the form of inequality and environmental damage. Suddenly, those who cared about people and the planet themselves became a profit opportunity.

This is the part about ESG that worries me; asset managers are pushing out ESG products as if they are mother’s pies that will deliver better results than non-ESG companies.

The facts show that oil and gas companies, and arms producers, are currently reaping super-profits, and no one can say they are fully ESG-compliant. Cynically put, ESG standards for companies so far are all about disclosure, but not really about compliance.

As inventor Thomas Edison said, “invention is 1 per cent inspiration and 99 per cent perspiration”. Truly delivering net zero and combating social and environmental injustice requires mostly perspiration, which means that real people and companies have to deliver, whereas financial wizards can just claim they are doing their fair share by policing ESG.

ESG is not a scam, but much work remains to define it

In other words, I will believe GFANZ when its members first share how they themselves meet net-zero standards, and treat their customers and employees fairly, rather than simply demanding it of their borrowers. Doctors, heal thyself first.

As for EMDEs, the ESG hard work is making sure they have the governance capacity to deliver on social and environmental aims.

ESG is not just a private-sector project, but a partnership between companies, governments and communities that recognises huge barriers to change at every level. Perspiration will only begin when the top leaders show they are walking with everyone else, rather than just talking about it.

Andrew Sheng writes on global issues from an Asian perspective