Advertisement

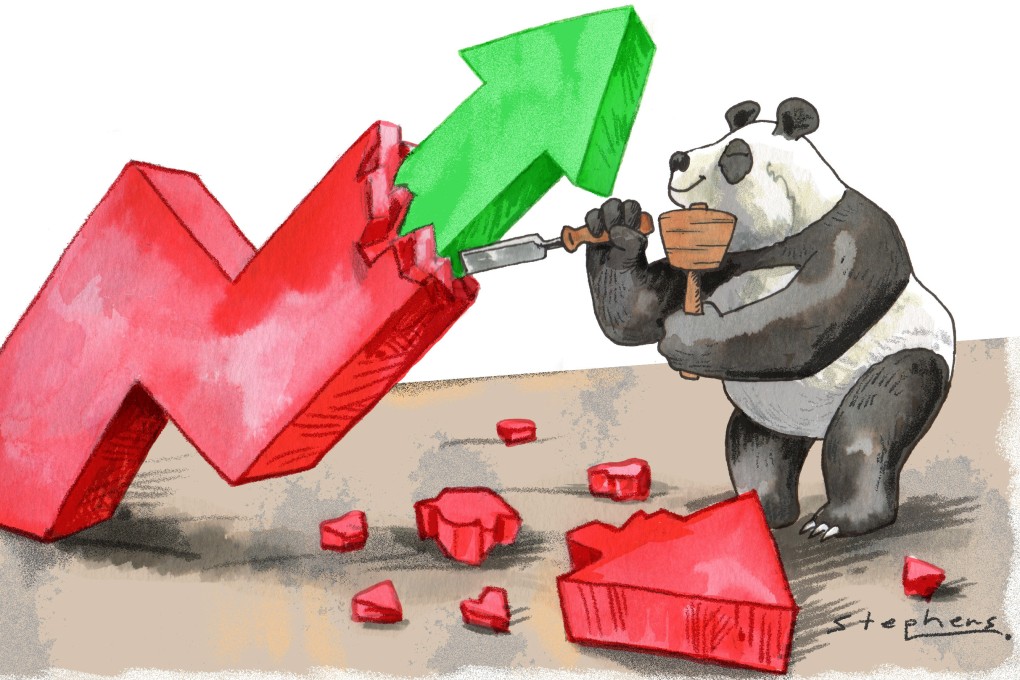

Opinion | Why there is good cause for optimism about China’s economy over the next decade

- Beijing has accepted that a slowing economy is the price to pay for quality growth and saving lives

- The economy looks set to return to normal for the rest of 2022, and then grow at an average annual rate of 5.5 per cent for at least another decade, even with a number of uncertainties

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

5

Beijing set the target for economic growth at around 5.5 per cent for 2022, the lowest in decades. This is because of a shift in emphasis from quantity to quality of growth. However, improving the quality of growth, for example through providing clean air and water for all, frequently results in negative value-added at market prices, and will therefore reduce the GDP growth rate. The Chinese government is perfectly willing to make such a trade-off.

Unfortunately, in the second quarter, a wave of Covid-19 led to extensive lockdown measures across Shanghai. Even though Shanghai’s shares of China’s gross domestic product and industrial value-added are relatively small, at 3.78 per cent and 2.88 per cent respectively, the city is pivotal to the economy because most major domestic and international supply chains pass through it.

If Shanghai stops, the rest of the country struggles to continue. As a result, second-quarter GDP growth fell from 7.9 per cent a year ago to 0.4 per cent. One lesson to be learned from the Shanghai experience is that a full, parallel and independent domestic supply chain should be developed outside the Shanghai region, perhaps in Chongqing, to avoid a recurrence of the disruption.

Advertisement

For the first half of 2022, the Chinese economy grew by 2.5 per cent. To achieve the 5.5 per cent target for 2022, growth will have to reach an average of 8.5 per cent for the second half, which does not appear possible.

However, the economy will return more or less to normal in the third and fourth quarters, and China should achieve 5.5 per cent growth for the second half, and thus 4 per cent for 2022 as a whole. The economy will still be doing better than many developed economies, which are heading into recession.

Advertisement

There may well be efforts to catch up in the last two quarters. The 20th Party Congress will be held later this year. That should focus the attention of provincial and regional leaders, plus the heads of large state-owned enterprises, on achieving a good economic recovery.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x