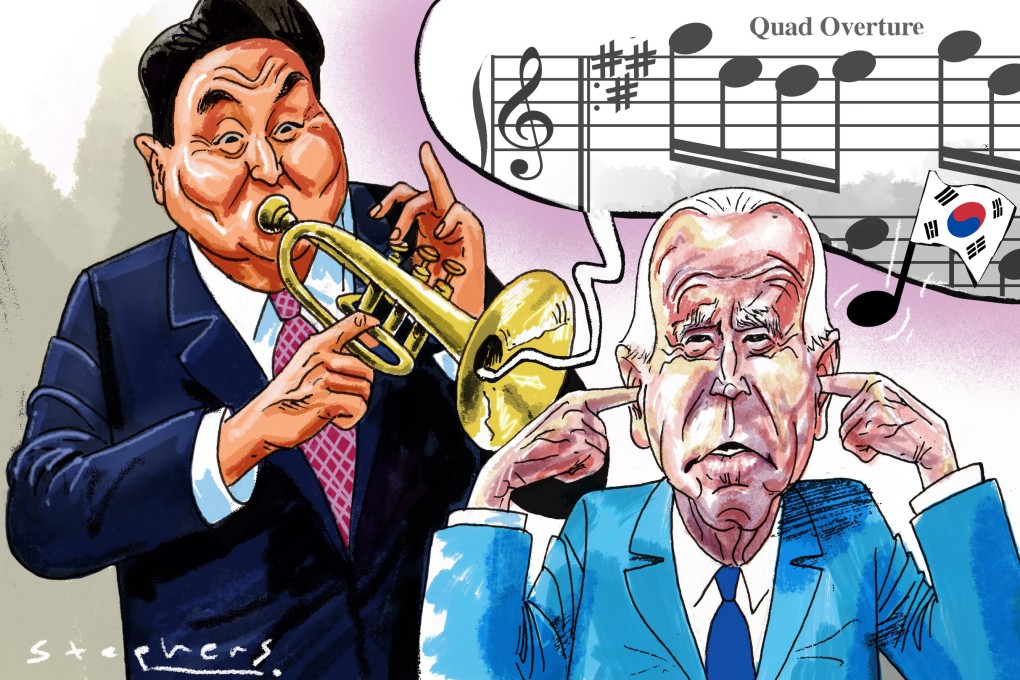

Opinion | Why South Korea’s Quad overtures are falling on deaf ears

- South Korea’s new president has ambitions for his country as a ‘global pivotal state’ and is courting closer defence ties with the West

- But the Biden administration is wary of letting South Korea join the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, which could aggravate relations with China

In an essay published in February, South Korea’s President Yoon Suk-yeol said: “This is a moment of change and flux in international politics. It calls for clarity and boldness, and for a commitment to principles.”

A presidential candidate at the time, Yoon argued that his country should become no less than a “global pivotal state”, which advances “freedom, peace, and prosperity through liberal democratic values and substantial cooperation” with like-minded powers.

Yoon’s tilt towards the West is significant when some in Washington are calling for the establishment of a “Pacific Nato” to counter a resurgent China. So far, however, the Biden administration has resisted adding South Korea to the Quad, perhaps to avoid escalating the cold war in Asia.