Advertisement

Opinion | How the narrative of an all-powerful government hurts China’s image at home and abroad

- The story of the unitary, all-powerful central government worked in the past, but it is failing to keep up with today’s complex realities

- Such an oversimplified message undermines people’s confidence in tough times and provides a convenient tool for unjustified criticism of China

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

21

On July 8, former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe was assassinated while giving a public speech in Nara. The following day, President Xi Jinping delivered a message expressing deep sadness over Abe’s death and offering condolences to Abe’s family. Xi also said Abe had made great contributions to the improvement of Sino-Japanese relations.

That last statement caught me by surprise. As far as I can remember, the later years of Abe’s tenure were saturated with criticism of him by the Chinese media. The issues ranged from a refusal to acknowledge past war crimes and efforts at militarisation, to Abe’s cosy relationship with US president Donald Trump. I think it’s fair to say Abe was thoroughly demonised in the Chinese media at that time.

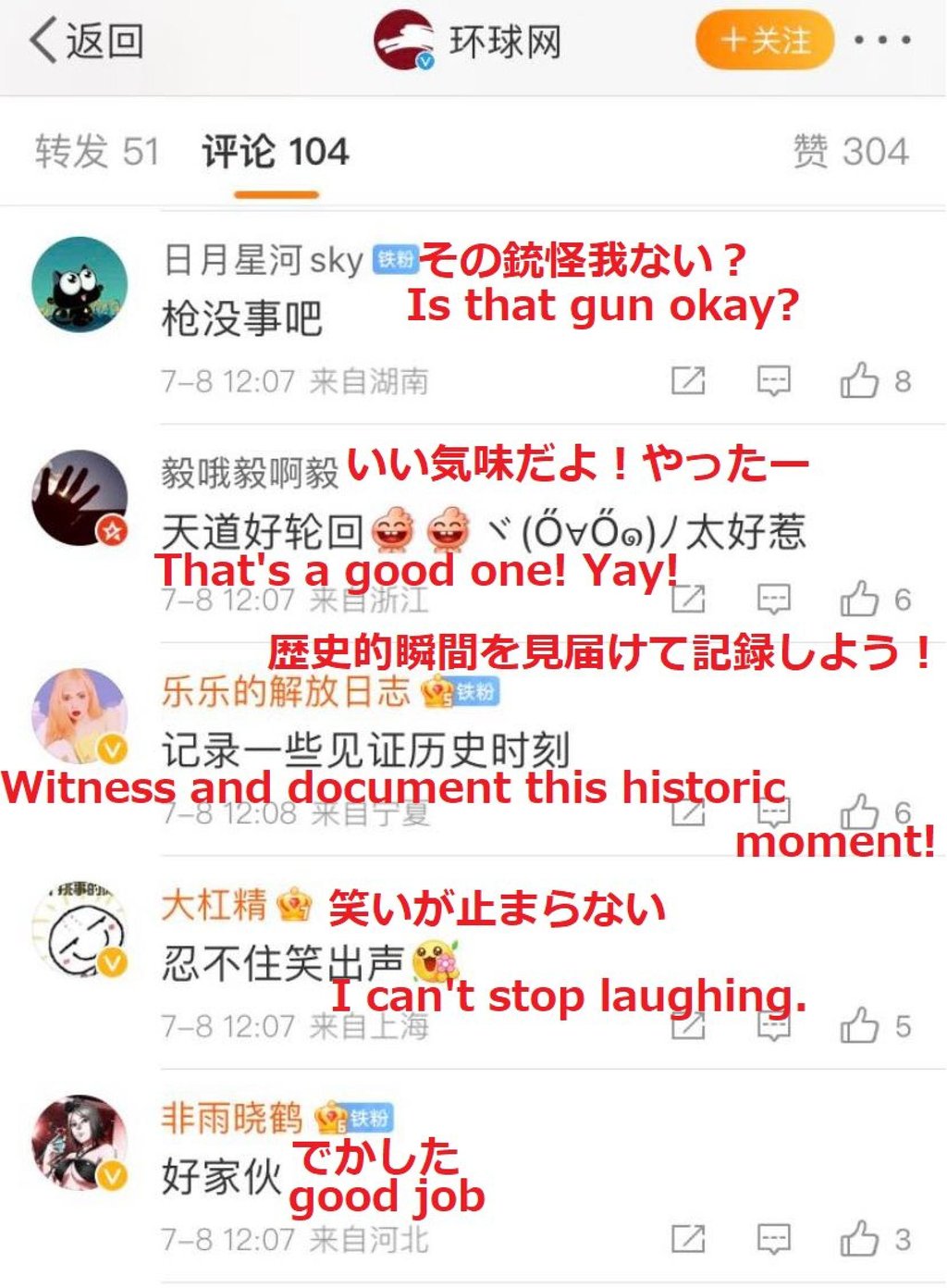

Thus, it was not a surprise that huge numbers of nationalist netizens came out to cheer after Abe’s death. It was also clear to me that such comments could cause people from other countries to view China in a worse light. The nationalists say they were exercising free speech, and why shouldn’t they be proud of it?

Advertisement

However, on this issue, they are wrong because their speech reflects badly on the country. China purports to control online content, meaning it censors what it believes to be harmful content, and anything not censored is seen as being implicitly condoned by the government.

In other words, the government owns the messaging because it controls it. So, when the internet exploded with antagonising comments about Abe’s death, running counter to Xi’s official statement of condolence, what were people to think?

A reasonable person could reach one of two conclusions. First, maybe the nationalists were stating the government’s real position. They were expressing what the government thought but could not say out loud. If true, this would be terrible for China’s national image.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x