Opinion | How Beijing’s belligerence over Taiwan is connected to a Belt and Road Initiative in distress

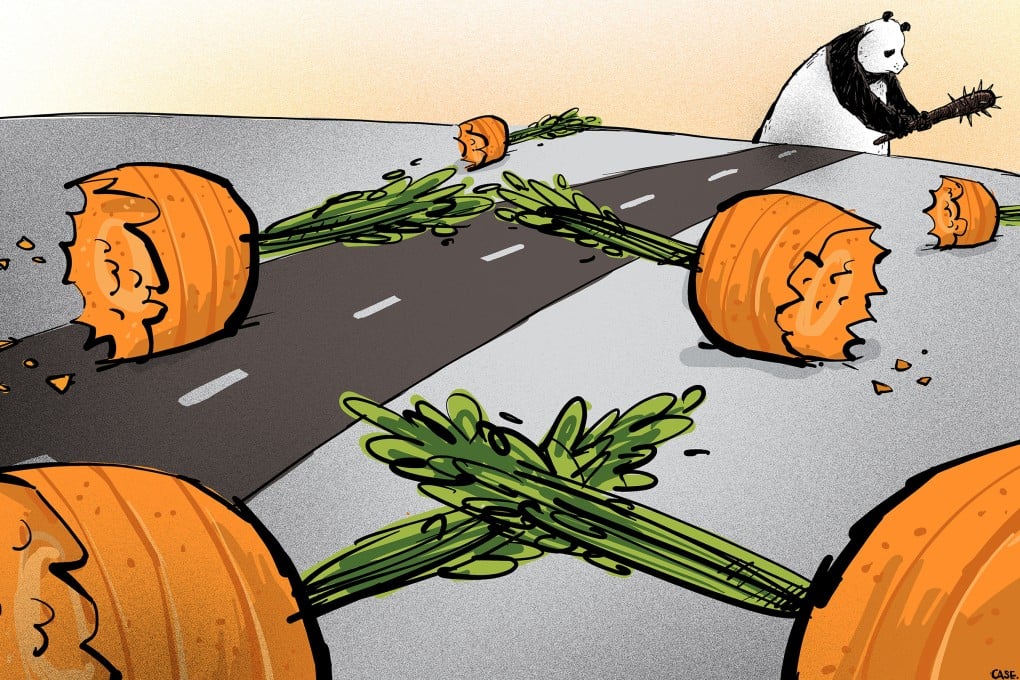

- For years, China focused on economic matters both at home and abroad, with the Belt and Road Initiative exemplifying that approach

- But as its economic influence encounters roadblocks, there are signs of a pivot in Chinese diplomacy towards geopolitical wrangling and militarism

Meanwhile, many developing countries were envious of its investment-driven growth model. The solution was to use Chinese money, muscle and manpower to build swanky infrastructure overseas.

At first, it was a big hit. People from Tunisia to Tajikistan looked forward to the arrival of posh highways, tall towers and ornate stadiums. But the returns did not quite follow. Many hosts of belt and road projects struggled to emulate the Chinese growth model because, simply put, they were not China: they lacked its bureaucratic capacity, cheap skilled labour, land, water and electricity.

But the port lost US$300 million in six years and the airport was so unproductive that it could not even cover its electricity bills at one point. Meanwhile, the conference centre cost over US$15 million to build but has remained largely empty.