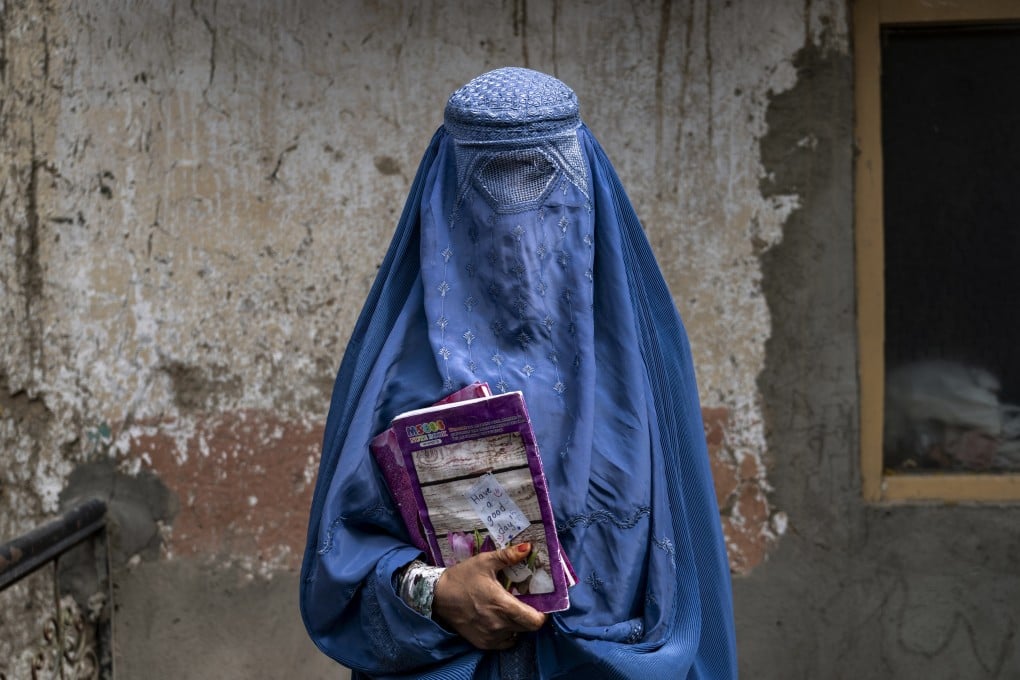

Opinion | After a year of Taliban rule, Afghan women are systematically disappearing from public life

- Following the US’ withdrawal, the Taliban government has significantly limited women’s ability to earn a living, access education and escape violence

- The international community must act rather than merely condemning the erosion of Afghan women’s rights

Following the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, women in the war-torn country were granted more rights than they had previously had under the Taliban regime, and they enjoyed a measure of freedom, in terms of how they wanted to dress, and where they wanted to study and work.

The Taliban’s strict interpretation of Islamic sharia law has, in fact, left no room in public life for women, who comprise around 48 per cent of the country’s population.

By replacing the Women’s Affairs Ministry with the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, the Taliban has dismantled the system that was designed to respond to gender-based violence. It has also failed to appoint any women to its new cabinet, effectively denying women their right to take part in the country’s political life.