Opinion | The UK’s next prime minister will preside over a bleak economy

- The leadership race has been driven by debate about taxation, inflation and the Thatcherite legacy

- It bears noting that the tax-cutting plans of Liz Truss, the front runner, are expected to translate into lower public spending and even austerity

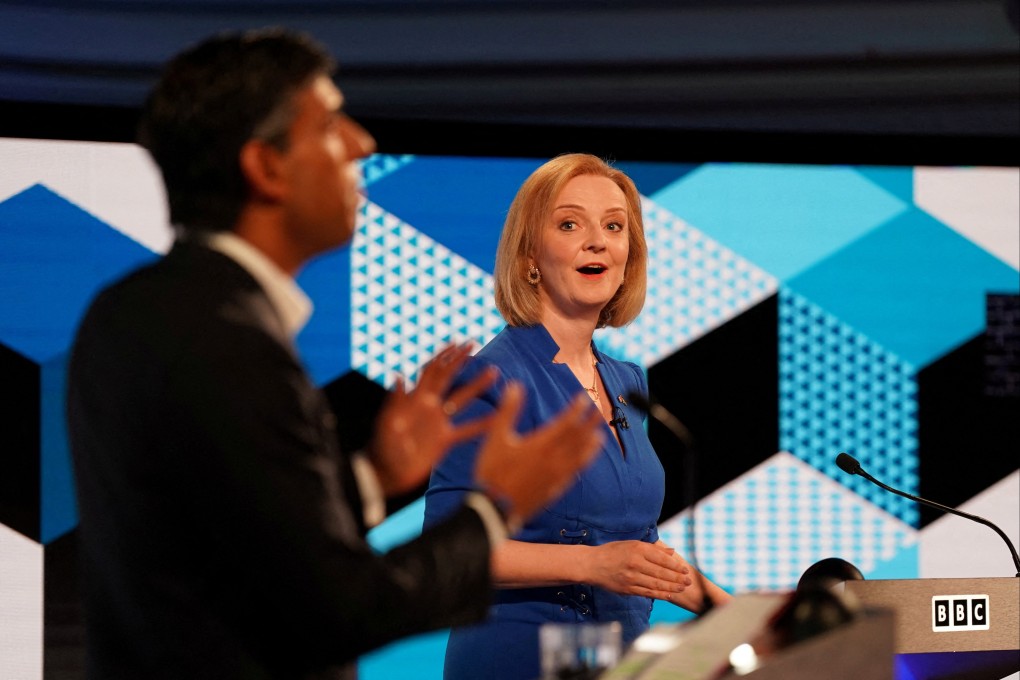

British Foreign Secretary Liz Truss, the front runner to succeed Boris Johnson as prime minister, made the remarkable claim last month that an end is needed to what she called a failed consensus “peddling a particular type of economic policy for 20 years” that hadn’t delivered.

While such criticism would not be unusual coming from an opposition politician, her statement is surprising in that it is the Conservatives who have been in office for the past dozen of the years in question, with Truss herself serving as a minister for much of that period, including in economic portfolios.

Truss argues that, just as Thatcher tested widely held policy beliefs in the 1980s, it is time for her to do the same in the 2020s with tax cuts. Truss is therefore heavily critical of Sunak’s period of office, particularly his tax increases.

She has pledged to “start cutting taxes from day one”, reverse April’s rise in national insurance, and abolish next year’s corporation tax hike from 19 to 25 per cent.

She has not explained how she would pay for the £30 billion (US$35.12 billion) in tax cuts she has promised, but insists they can be paid for within the “existing fiscal envelope”. Truss insists that cutting taxes will help curb inflation, and that “what is not affordable is putting up taxes, choking off growth, and ending up in a much worse position”.