Advertisement

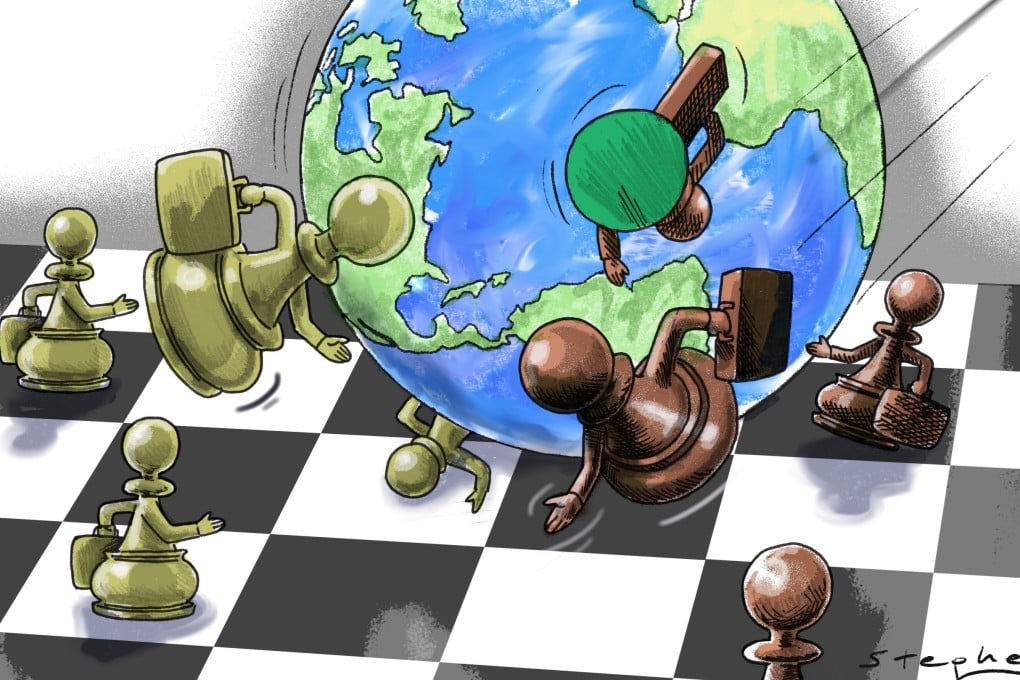

Opinion | In a world driven by geopolitics, keeping the doors of trade open will be a challenge

- The business world can no longer ignore geopolitical trends as supply chains are diverted, markets are marred by red tape and companies are forced to take sides over contentious issues

- Businesses will need to be prepared to navigate this fraught new geopolitical landscape

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

3

For two-and-a-half decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the world was propelled by the dual forces of globalisation and multilateralism. Gone was the debate over political ideology – once dubbed “the end of history” by Francis Fukuyama, a characterisation that has increasingly been challenged – with trade, growth and economic integration across regions and under international institutions the norm.

Geopolitics took a back seat as democratic and authoritarian regimes alike resorted to deepening commercial, even sociocultural ties, in a radical departure from the world separated by the Iron Curtain in the latter half of the 20th century. It was intuited that business and money would speak louder than ideologically loaded rhetoric.

Yet recent events suggest that the era of seemingly post-political globalisation has now come to an unpleasant – albeit by no means abrupt – halt. Brexit and Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 US presidential election were wake-up calls signifying a backlash from those who had been left behind by the train of unrestrained growth.

Advertisement

The Covid-19 pandemic has prised countries apart from one another – concurrent to the escalating US-China tensions that are undoing decades of progress in seeking common ground. From tensions over the Taiwan Strait to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the prospect of war is no longer abstract to the affluent.

Geopolitics has returned to the world stage. In a recent survey of Hong Kong’s high-net-worth individuals by a Swiss private bank, the top concern for most were geopolitical tensions. These can no longer be stalled or smoothed over by the transactional, monetary arrangements that lined the pockets of the elite across all parties.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x

.png?itok=bcjjKRme&v=1692256346)