Multilateralism isn’t dying – just the version led by the US

- America’s shift away from diplomatic solutions towards military ones and its growing debt mountain have undermined its leadership

- The problem is that the US-led system is failing but a new multipolar multilateralism has yet to be born

Encyclopaedia Britannica defines it as the “process of organising relations between groups of three or more states” bound together by their common interests, reciprocity and similar values or ideology. This post-war definition was formed by the G7, the Group of Seven that comprises the United States as de facto leader, Canada, United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy and Japan.

Since reconstruction of the world economy was the priority, the rest of the world was happy with the unipolar multilateralism, focusing on trade, finance and development. Geopolitics was constrained during the Cold War since the Soviet bloc was strong militarily but weak economically. Development went reasonably well under Pax Americana.

Brace for a Great Reset as new voices challenge Western world order

We saw this after the 2008 global financial crisis, when the G7 recognised that they must accommodate new powers and the G20 was formed, to include China, Russia, India, Indonesia, Brazil, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, Türkiye, Argentina, Mexico, South Korea, Australia and the European Union.

Polarisation has stemmed from a seismic shift from diplomacy and negotiations towards the weaponisation of finance, sanctioning of media, individuals, corporations and country, and military clashes.

Global inequality thought leader Branko Milanovic asked recently: “Does the United Nations still exist?” Development occurred with peace, but the UN was unable to keep the peace when its rules were openly violated.

Milanovic cited two other reasons the UN is failing – a broadening of its goals into areas that could be handled by national and local governments, and a clear lack of resources to deal with key issues such as climate change and social inequality.

At the heart of the multilateralism debate is who ultimately funds global public goods, such as security, health, climate action and the addressing of local imbalances. No taxation without representation.

Whose world? What order? Time has passed for West to call the shots

The unipolar system led by the US was followed as long as it provided the global policing, key financial and technological standards and led in terms of education, scientific research, media and finance. The rest started having second thoughts when there was a distinct shift away from diplomatic solutions towards more military solutions, such as in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, and sanctions.

Since the US continues to run large fiscal and current account deficits, creditors can expect this liability to increase. As a serial borrower, the US cannot sustain the unipolar position. Sooner or later, creditors will want more voice on how such debt could be repaid or at least managed safely for the world.

In sum, unipolar multilateralism has an option date that is expiring. A multipolar multilateralism is yet to be born. This is why we are in this mess.

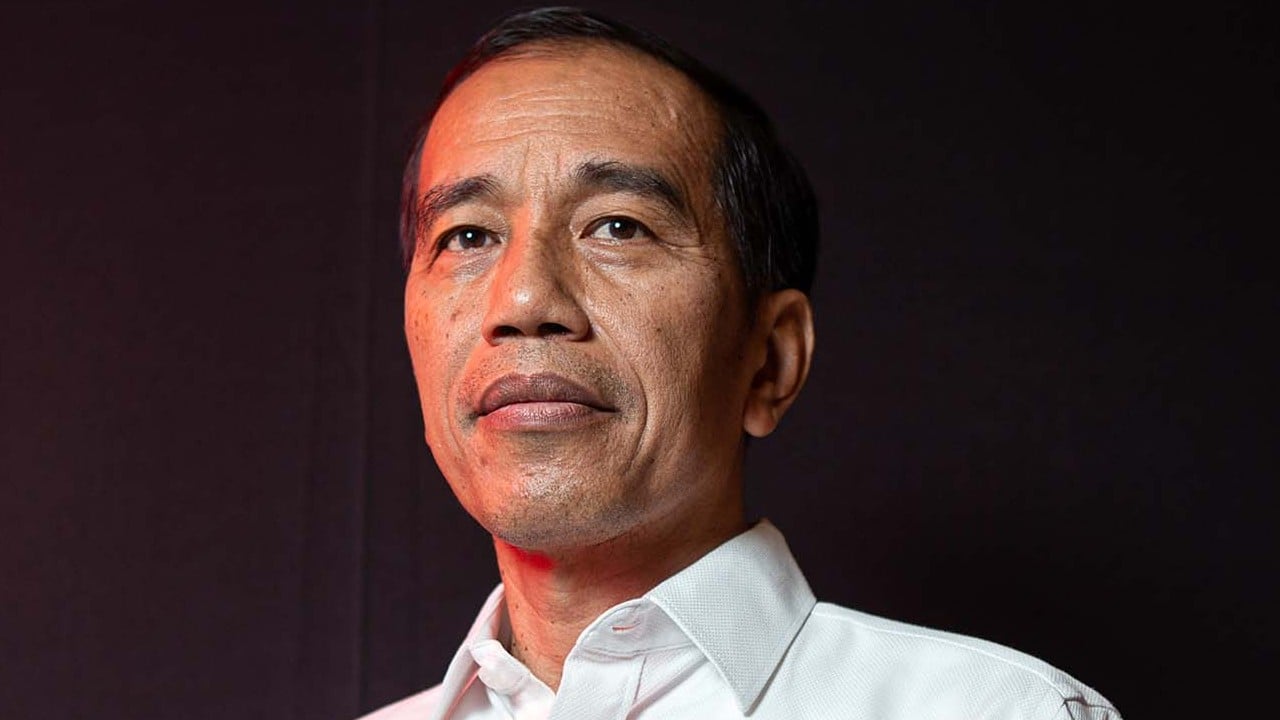

Andrew Sheng writes on global issues from an Asian perspective