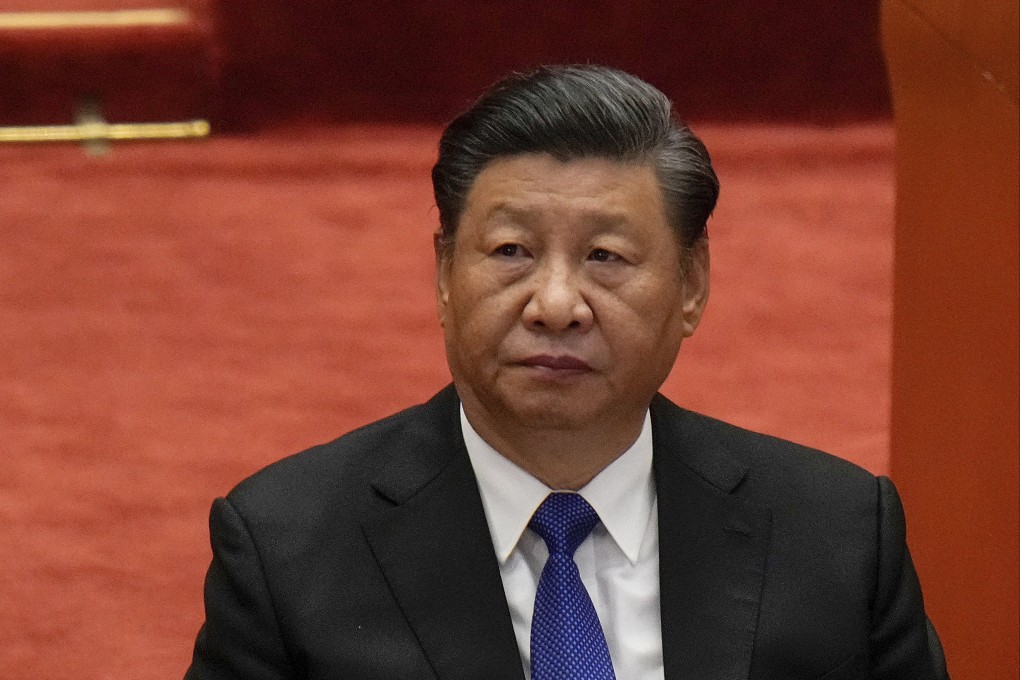

My Take | Xi Jinping and the revenge of the ultra-leftists

- The president’s extended tenure in power is more about his programmatic mission – which may be argued, though rarely acknowledged, to have made bedfellows with China’s so-called New Left – than the whims and ambitions of one man

In Western discourse, leftists in China are usually mentioned in the same breath as ultra-nationalists and rigid ideologues. That’s true to an extent. But the deeper thinkers and more thoughtful party leaders among them also offer a critique of contemporary China and a programme on how to rectify its most deep-seated problems, or contradictions in the lingo of Marxism.

This programme provides both the ideological and practical justifications for President Xi Jinping’s policies from the time he took office and which are likely to continue with his norm-breaking third term in power. But while this programme may be clothed in Marxist-dialectical jargon, it makes strange bedfellows with the critique of the Chinese economy by mainstream economics, a perspective which is shared by many critics of China in the West today.

In this sense, Xi’s extended tenure shows a determination to address and rectify the objective problems or “contradictions” plaguing contemporary Chinese society and economy. This does not mean that Xi and his leftist supporters and cheerleaders are right, but it is necessary to understand their policy responses go beyond mere power struggles – the usual narrative of the Western media – but rather involve substantive policy debates and choices.

The mainstream economic critique of China

For more than three decades, the country’s phenomenal growth has been driven by investment and exports, backed by heavy state subsidies and discrimination against foreign firms, including closing key sectors to foreigners. That is made possible through financial repression of the savings of ordinary people, who have no choice but to put their hard-earned money in low-interest bank deposits, which become a constant source of low-cost financing for the state to allocate resources to provide for the different economic sectors, and drive and maintain a trade surplus with the United States.

Instead of benefiting ordinary Chinese, profits from the trade surplus have been recycled through the buying of US sovereign debt. Therefore, they benefited American consumers and borrowers, at least until the last global financial crisis. In the past decade, though, US-China relations have been going through a painful and dangerous retrenchment.

As Michael Pettis, a noted economist at Peking University, wrote recently in this newspaper, “As the productivity benefits of additional investment declined, China’s high investment level would necessarily lead to a rising debt burden.

“This is what eventually happened to every country that has followed this growth model: a period of rapid, sustainable growth was followed by a period of still-rapid but unsustainable growth, driven by surging debt. This started to happen to China at least a decade ago.”