Ukraine war: an emotional Europe is playing right into the US’ hands

- With no exit strategy from the war, backfiring sanctions and rising risks of a nuclear escalation, Europe has effectively ceded decisions to the US

- Meanwhile, economic loser Germany’s decision to rearm awakens old fears

As the Ukraine war drags on, I am reminded of the late Yale University professor Nicholas Spykman’s assertion that “whoever rules the Rimland commands Eurasia, and whoever rules Eurasia controls the destinies of the world”.

Zbigniew Brzezinski’s 1997 article “A Geostrategy for Eurasia” is also essential reading for anyone wanting to understand US policy on Europe. The former US national security adviser noted that “Eurasia accounts for 75 per cent of the world’s population, 60 per cent of its GNP [gross national product], and 75 per cent of its energy resources. Collectively, Eurasia’s potential power overshadows even America’s.”

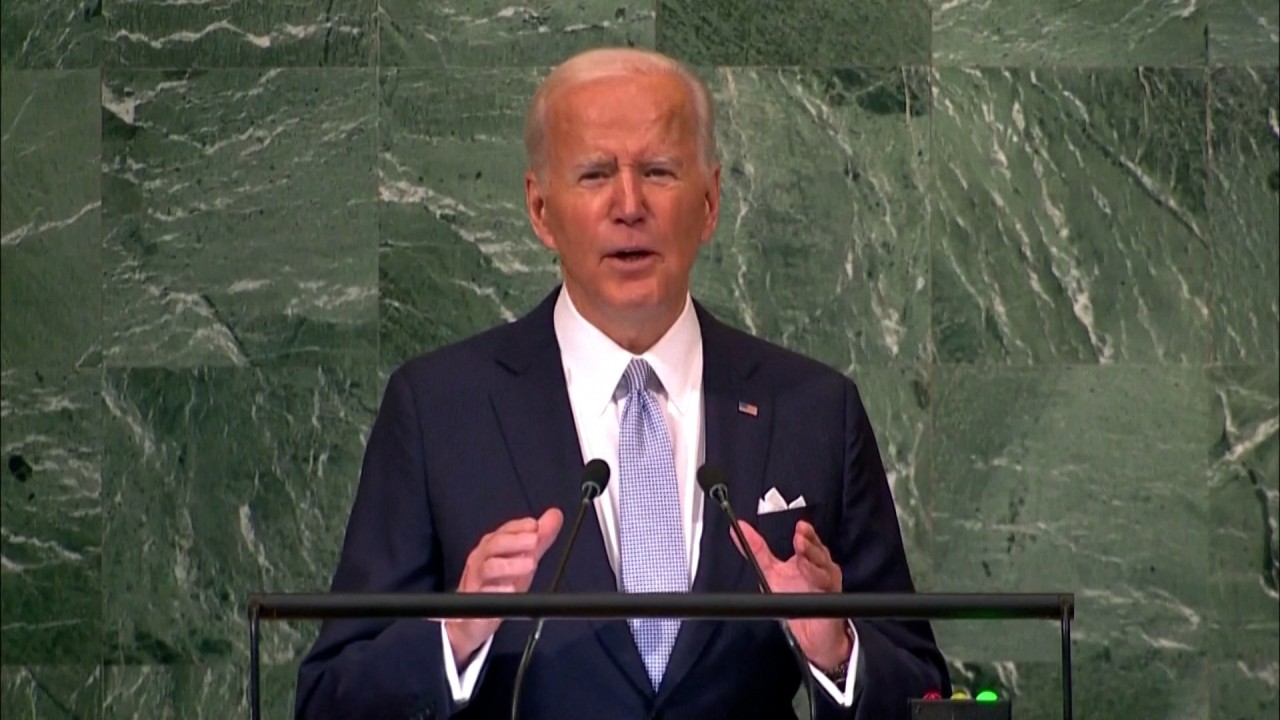

Spending time in Europe last week made me realise how emotions are clouding logic in the debate over the Ukraine war.

Second, the economic sanctions against Russia have backfired, with European households paying more for energy and therefore facing higher inflation, while Russia’s exports have recovered with much less economic damage than expected. The International Monetary Fund forecasts that the Russian economy will shrink by just 3.4 per cent this year, compared with a 35 per cent drop in real gross domestic product for Ukraine.

The Ukraine war, therefore, is a war fought within Eurasia that will decide whether Eurasia can decide on its own security.

Eurasia, as a continental mass, has enough food and energy for all, except that resources are not divided equally. Geographical space was complicated by emotional space, as neighbours fought over religion, race or tribal concerns that often defy logic. Continental Europeans remember how Britain, an offshore island, kept playing divide and rule so no European power could challenge the British empire. History seems to be repeating itself with the US playing the same game.

Eurasia in turmoil: how China’s passivity foments the chaos

All this raises the question of whether any nation-state can be totally sovereign in an interrelated world. All International Monetary Fund members know that when they get into trouble financially, they have to cede sovereign decisions to the fund to get financial aid. Small countries that have powerful neighbours know they cannot act against their neighbours’ interests without costs. Realistically, no sovereign country is totally independent in an interdependent world.

Ukraine’s fate today is to fight to the last man. When that happens, there will be no principle left to defend. If we take that logic to nuclear war, what is the moral worth of defending one’s sovereignty when everything can disappear in a nuclear annihilation?

As long as emotions run high, the war will continue. Cold logic for peace can only come when everyone is looking at paying the ultimate price for the foolishness of senseless slaughter.

Andrew Sheng writes on global issues from an Asian perspective