Advertisement

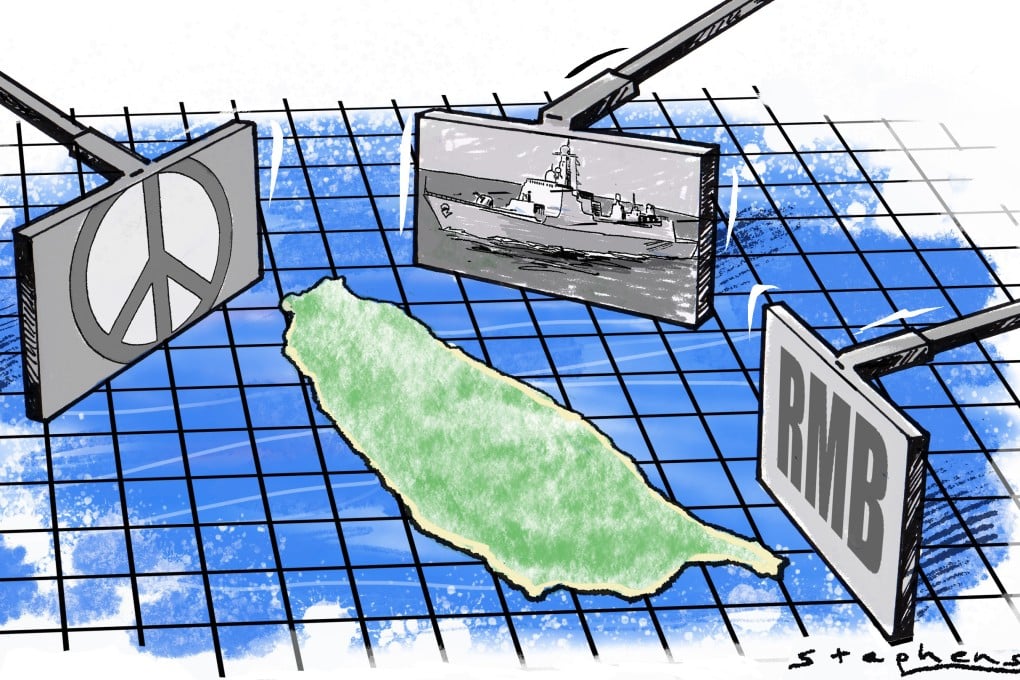

Opinion | The next Taiwan Strait flashpoint? Beijing sees coercive force as peaceful nudging but the US does not

- Where Beijing sees grey-zone activity and psychological warfare as peaceful means to push for unification with Taiwan, for the US, coercion is clearly stipulated in the Taiwan Relations Act as something it opposes and must act against

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

25

President Xi Jinping’s report to the 20th party congress did not raise many new concepts on the Taiwan issue. But the emphasis, one could argue, has definitely shifted.

While “peaceful reunification” and “one country, two systems” are still hailed as the best options for Taiwan, the call to fight against “interference by external forces” has gained significantly more prominence. For most observers, the question of Beijing’s use of force on Taiwan is still the most critical. Xi’s report maintains that Beijing will not abandon the use of force and will keep all options on the table.

The concept of Beijing’s use of force on Taiwan has been frequently discussed. Most assume it means a direct military operation. Given the political reality, the 20th party congress meeting was never going to be a watershed event in China’s genesis on national unification.

Advertisement

Beijing will not pronounce a deadline for unification, as that only ties its hands. This is especially because the conditions for unification, including Taiwan’s domestic politics and US policy towards Taiwan, are all out of Beijing’s control.

But China’s desire and push for unification is real, and accelerating. It is fair to say Beijing has left no stone unturned in promoting reunification. Economic integration, such as through the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement signed in 2010, used to be a primary area of efforts. For believers of political integration or absorption led by economic integration, weaving Taiwan’s economy closely with the mainland’s is the best way to achieve unification peacefully.

Advertisement

Social integration has also been attempted exhaustively, such as through the “26 measures” and “31 measures” (preferential policies for the Taiwanese). But since the 2016 election of the Democratic Progressive Party, none of these has rendered the intended result.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x