Opinion | Shrinking role of China’s public intellectuals will hold back country’s rise

- After a rise to prominence in the early 2000s, the country’s public intellectuals have lost credibility as tolerance for criticism of China has shrunk

- Suppressing these people leaves fewer voices to suggest new ways forward, with top leaders stuck in an echo chamber with little ability to correct mistakes

The Weekly said China was at a point “when it most needs public intellectuals to be on the scene and to speak out”. The list was circulated widely and popularised the term gongzhi, or public intellectual. The reputation of gongzhi quickly rose, but its glow soon faded.

Two months later, the hardline Liberation Daily attacked public intellectuals because their independence drove a wedge between the intellectuals and the party. It also claimed the concept was a foreign import. The article was then reprinted in the People’s Daily.

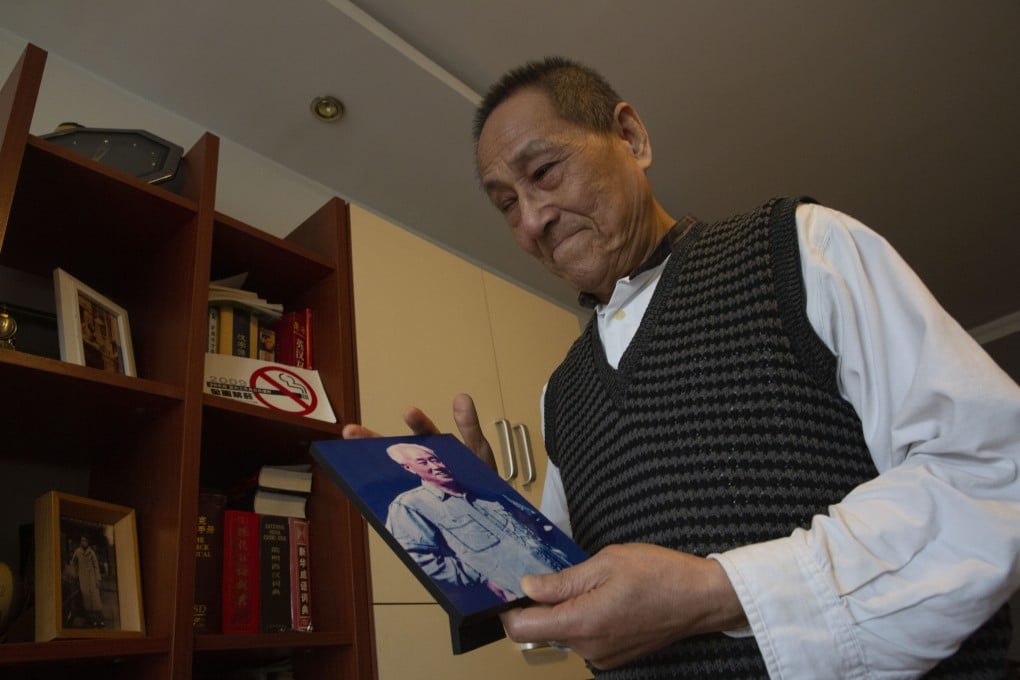

Of course, ancient China had its share of public intellectuals, or the equivalent thereof. Confucius was perhaps the first and most renowned one as he not only taught his philosophy but also offered advice to various statesmen. In ancient times, such scholars had the responsibility to advise top officials and even emperors.