Advertisement

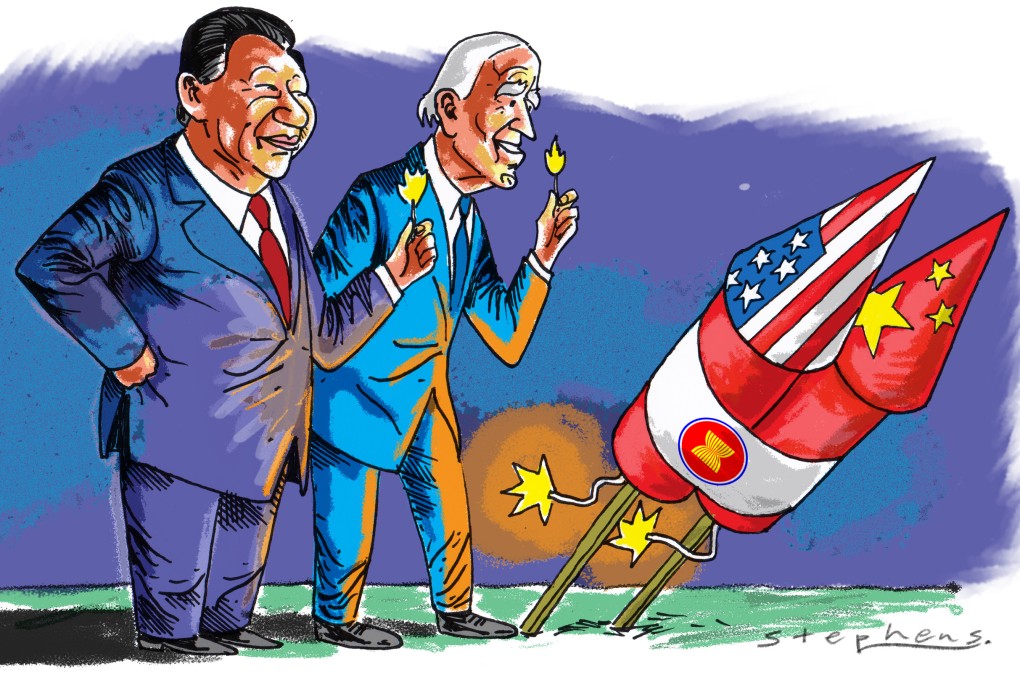

Opinion | Why Southeast Asia is desperate for a US-China detente

- For Asean, a truce will put to rest fears of a backyard military conflict, pressure of choosing sides and decoupling worries

- Ultimately, the region needs superpower cooperation to help it meet its challenges, from Myanmar’s crisis to climate change and terrorism

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

19

The current state of US-China relations was not in the fundamental interests of the two countries and peoples, and not what the international community expected, declared Chinese President Xi Jinping during his meeting with his American counterpart on the sidelines of the Group of 20 summit in Bali, Indonesia.

On his part, President Joe Biden underscored the need to prevent the US-China rivalry from “veer[ing] into conflict” and that “the United States and China must manage the competition responsibly and maintain open lines of communication”. He also agreed that both countries “must work together to address transnational challenges” such as climate change and terrorism, “because that is what the international community expects”.

Accordingly, Biden and Xi agreed to resume a wide range of institutionalised bilateral dialogues to deepen the scope for cooperation. The summit came after months of tension following US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, which unleashed a naval and diplomatic showdown between the two superpowers.

Advertisement

The fateful summit in Bali, which seemed genuinely cordial, was welcomed across the world. In Southeast Asia, which has hosted several summits this month, the Biden-Xi detente was met with relief. Regional states had been deeply anxious about the economic and geopolitical implications of unfettered rivalry between the US and China as they vigorously compete for strategic primacy in Southeast Asia.

The highly consequential and potentially fruitful meeting between Biden and Xi should not have come as a total surprise. On one hand, both leaders were operating from a position of strength. Xi has secured a historic third term as China’s top leader, while Biden has defied the odds in the midterm elections.

Advertisement

With Democrats holding onto the Senate, and narrowly losing the House, Biden has ended up as the best-performing Democratic incumbent in more than half a century. With their domestic positions secure for now, both leaders felt confident enough to extend an olive branch.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x