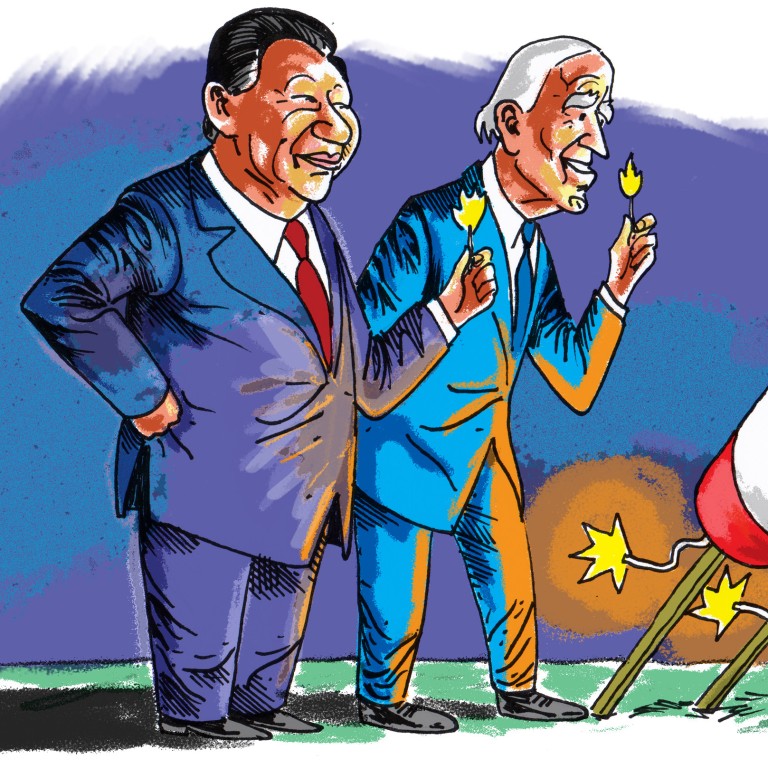

Why Southeast Asia is desperate for a US-China detente

- For Asean, a truce will put to rest fears of a backyard military conflict, pressure of choosing sides and decoupling worries

- Ultimately, the region needs superpower cooperation to help it meet its challenges, from Myanmar’s crisis to climate change and terrorism

On his part, President Joe Biden underscored the need to prevent the US-China rivalry from “veer[ing] into conflict” and that “the United States and China must manage the competition responsibly and maintain open lines of communication”. He also agreed that both countries “must work together to address transnational challenges” such as climate change and terrorism, “because that is what the international community expects”.

With Democrats holding onto the Senate, and narrowly losing the House, Biden has ended up as the best-performing Democratic incumbent in more than half a century. With their domestic positions secure for now, both leaders felt confident enough to extend an olive branch.

During an emphatic speech at the East Asia Summit in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Biden promised to work on “keeping lines of communication open and ensuring competition does not veer into conflict”, said the White House.

Just days later, Indonesia, Asean’s de facto leader, hosted the G20 Summit, which paved the way for the US-China diplomatic breakthrough. It brough some relief to Southeast Asian nations, since the festering Sino-American relations in recent years has presented existential challenges on three levels.

Since China is a major trade partner and investor in many neighbouring countries, Asean members are deeply worried about disruptions to regional supply chains and innovation networks. In a recent impassioned speech, Singaporean Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan highlighted the deleterious impact of technological decoupling.

Without directly mentioning US sanctions, he warned of escalating threats to “open science, the fair sharing and harvesting of intellectual property, and a system in which we will compete to be most innovative, reliable and trustworthy” without being forced to choose between the two superpowers. He made it clear that no “self-respecting Asian country wants to be trapped, or to be a vassal or, worse, to be a theatre for proxy battles”, including in the realm of technology and investments.

Southeast Asian states prefer the two superpowers to cooperate, rather than engage in zero-sum rivalry, over economic development initiatives, especially given the depth of the infrastructure spending gap in the region.

In short, the fate of Asean members is largely tethered to the trajectory of US-China relations in the 21st century.

Richard Heydarian is a Manila-based academic and author of “Asia’s New Battlefield: US, China and the Struggle for Western Pacific” and the forthcoming “Duterte’s Rise”