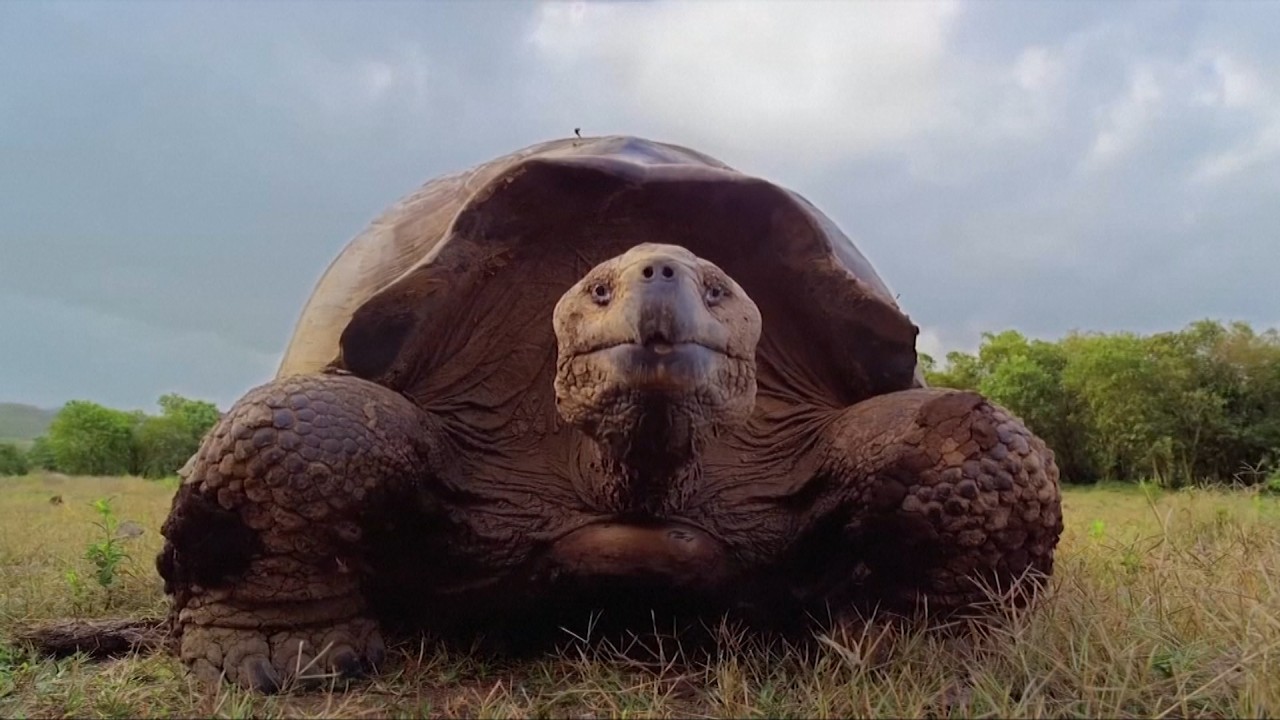

Nature is an asset: investors must do more to support biodiversity

- As stewards of global capital, investors are uniquely positioned to help build an economy that works with, rather than against, nature

- They can help shift capital flows away from businesses and projects that degrade the natural environment, towards regenerative and circular initiatives

The past 30 years have seen a bigger improvement in human prosperity than all the past centuries combined. We have built more roads, buildings and machines than ever before. More people are living longer and healthier lives, and access to education has never been better.

The average gross domestic product per capita has grown 15-fold since 1820. More than 95 per cent of newborns now make it to their 15th birthday, as opposed to just one in three in the 19th century.

But, such efforts should not be confined to the policy arena. Investors, too, must play a more active role. As stewards of global capital, they are uniquely positioned to help build an economy that works with, rather than against, nature.

Data shows that, from 1992-2014, the amount of capital goods – such as roads, machines, buildings, factories and ports – generated per person doubled. But the world’s stock of natural capital – water, soil and minerals – per person declined by nearly 40 per cent.

Recent advances in technology offer the promise of using natural capital more efficiently. Scientists estimate that the efficiency with which humans transform natural capital into GDP is improving at an annual rate of 3.5 per cent; for natural capital drawdown to halt, though, the efficiency improvement would have to climb to 10 per cent.

It is worth noting that, by channelling investment to companies developing advanced environmental technology and services, the financial industry has helped improve efficiency in everything from energy use and agriculture to trade and transport.

But greater efficiency is unlikely to be enough. Building an economy in harmony with nature requires governments, regulators, corporations and consumers to all play their part.

Once these targets become national policy, policymakers and regulators could quickly establish a framework for biodiversity protection and disclosure. Businesses and investors can ill-afford to ignore the shift in attitudes.

Intensifying political and regulatory efforts are a step in the right direction. But policymakers cannot turn the tide on their own.

But such efforts will come to nothing without an accompanying revolution in biodiversity-related capital.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development estimates that investments aimed at protecting biodiversity stand at less than US$100 billion a year. That compares poorly with what climate change attracts (US$632 billion), or with the US$500 billion per year invested in activities that harm nature, such as fossil fuel extraction and agricultural subsidies.

Historically, biodiversity finance has tended to focus on raising money for conservation. More recently, however, there has been a steady increase in biodiversity and natural capital investment.

Companies must target net zero biodiversity loss, not just climate change

Such strategies invest in companies developing products and services targeted at minimising biodiversity loss and restoring nature, and aim to capitalise on the potential for long-term capital growth.

In recent years, the asset management industry has launched high-profile funds investing in companies specialised in biodiversity restoration and ecosystem services, with nine out of 11 such funds having debuted since 2020.

Assets under management in this group have more than doubled to US$1.3 billion from just US$525 million at the start of the decade.

Such investment should also help embed more sustainable business practices across a whole value chain, involving industries such as agriculture, forestry, information technology, fishery, materials, real estate, consumer discretionary and staples, utilities and pharmaceuticals.

The Food and Land Use Coalition found that efforts to transform food and land use could create a biodiversity and nature market worth US$4.5 trillion by 2030.

By developing a thriving natural capital market, investors can help shift capital flows away from businesses and projects that degrade the natural environment and towards regenerative and circular initiatives.

Nature has always been the economy’s most important asset. It is time investors recognised that.

Laurent Ramsey is managing partner of The Pictet Group