Advertisement

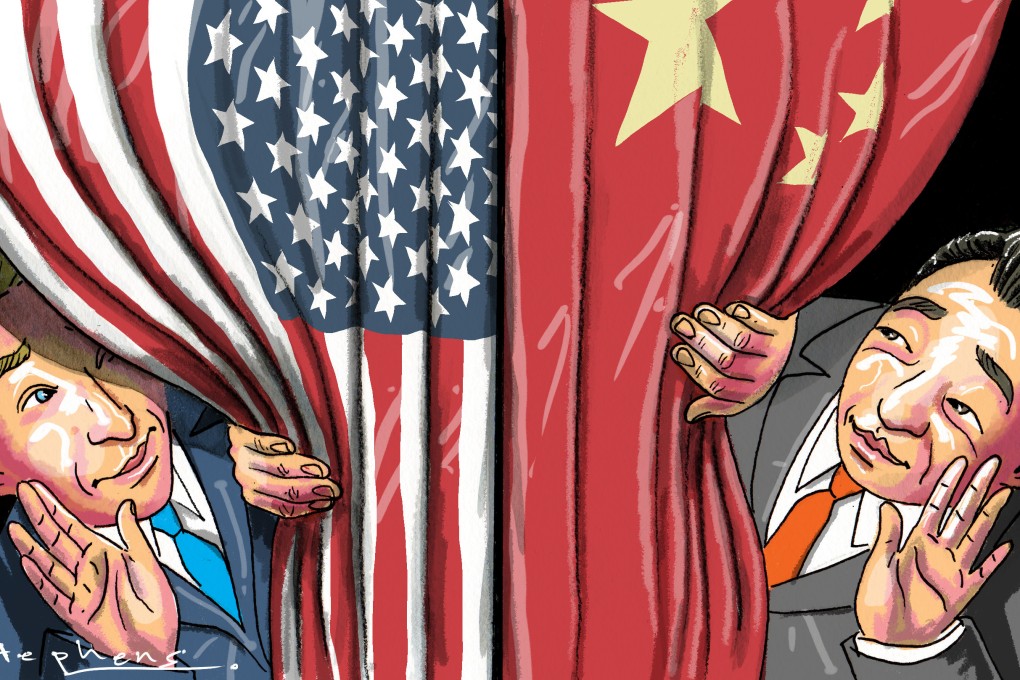

Opinion | US and China must bring back constructive people-to-people exchanges

- Amid US-China tensions, as intercultural exchanges and academic exchanges drop off, constructive dialogue between the two peoples is needed more than ever

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

3

US-China disagreements over a host of issues, including Hong Kong, Taiwan, Xinjiang and Tibet, are complicated. The issues demand thoughtful discussions rooted in mutual respect, not shrill, one-sided remonstrations.

Relations between these two most powerful nations in the world are at a recent low. In the last six years, anti-China rhetoric rooted in American political fevers has left many peace-loving Chinese-Americans facing scorn, even violence, from fellow Americans.

In trying to root out spies, the US government has investigated many Chinese scholars (many in the fields of science, technology and engineering), with only a small percentage leading to convictions.

Advertisement

While it is vital to protect our nation from enemies (foreign or domestic), it is unwise to resort to myopic strategies smacking of racial profiling which only stir up fear, panic and suspicion among law-abiding Chinese-American scholars and loyal citizens. Recently, a wave of ethnic Chinese scientists, including world-leading structural biologist Nieng Yan from Princeton University, chose to leave America under this cloud of intercultural pressure.

China and the United States were sworn enemies until former US president Richard Nixon dramatically reached out to re-establish relations. Nixon stressed cultural exchanges and enrichment to help citizens of both nations see each other as fellow contributors to peaceful artistic expressions, instead of only as bitter enemies.

Advertisement

President Jimmy Carter advanced this policy with Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping and, in the 1979 accords, expanded interactions that promoted education and academic partnerships.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x

.jpg?itok=stF_8QDU&v=1712569635)